INTRODUCTION

The comedian, Mel Brooks, once uttered a quip for the ages: "It's good to be king!" The thrust of the statement was that those in power can do what they want. The Moore case challenges that notion when it comes to tax legislation by asking whether the Constitution of the U.S. places limits on the ability of Congress to tax what is essentially unrealized income.

THE CASE

The Facts

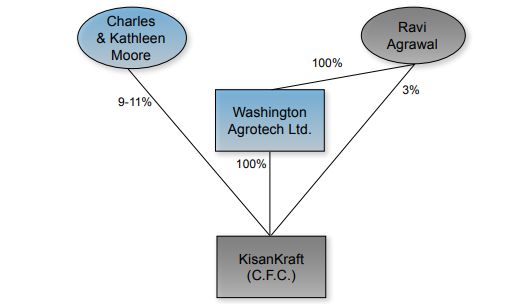

In 2006, Charles and Kathleen Moore invested $40,000 for an 11%1 stake in KisanKraft Machine Tools Pvt. Ltd., an Indian corporation in the business of farming equipment. KisanKraft was founded and controlled by a friend of Moores, Ravi Agrawal. Mr. Agrawal held 3% of KisanKraft directly and 80% through a wholly owned U.S. corporation. Throughout the Moores' involvement with KisanKraft, the company retained all of its earnings and profits and never made a distribution to its shareholders. Nonetheless, the Moores were liable for a tax known as the "transition tax," a major element in the change of U.S. tax law applicable to direct investment by U.S. corporations in foreign subsidiaries.

In very broad terms, prior law allowed a U.S. corporation owning at least 10% of a foreign corporation to claim an indirect foreign tax credit for corporate income taxes paid by the foreign corporation. This credit was allowed in addition to the credit allowed for dividends withholding taxes. In a chain of foreign corporations, the indirect foreign tax credit was allowed as dividends were distributed up the chain, so long as certain ownership thresholds were met. U.S. citizens and resident individuals could not claim the benefit of the indirect foreign tax credit.

The transition tax targeted previously deferred foreign earnings of certain foreign corporations with U.S. shareholders. It required a one-time increase in Subpart F income attributable to the deferred foreign earnings of certain U.S. shareholders. The tax applied to any 10% U.S. shareholder of a "controlled foreign corporation" ("C.F.C.") and foreign corporations with 10% U.S. corporate shareholders. A corporation that triggers either threshold and has deferred foreign earnings is known as "deferred foreign income corporation" ("D.F.I.C."). To incentivize compliance, Congress added deductions that reduce the tax rate to comparably favorable rates of 15.5% for cash and cash equivalents and 8% for all other assets.

The Moores were liable for the transition tax because they were 10% shareholders, and KisanKraft was a D.F.I.C. under either threshold (i.e., it was a C.F.C. and had a 10% U.S. corporate shareholder in Washington Agrotech).2

THE LAWSUIT

Although the Moores failed to pay the transition tax in 2017 (when the tax was introduced and became due), they amended their tax return for that year and paid the tax. They then sued for a refund. The Moores based their objection on the "Apportionment Clause" of the Constitution, which requires that direct taxes be levied on states in proportion to the states' populations. While the Federal income tax is a direct tax that is not proportioned on the basis of state population, the 16th Amendment exempts income taxes from this requirement.

In the Moores' view, they had been passive investors who had yet to see any return on their investment. They argued that the tax was therefore a direct tax but not a tax on income, as they had not realized any income. As a direct non-income tax, they believed that, for the transition tax to be valid, it needed to satisfy the Apportionment Clause.

The Moores also found issue with the transition tax's retroactive nature: a D.F.I.C.'s earnings from as far back as 1986 are taxable to its shareholders under the transition tax. This, the Moores claimed, violated the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

The apportionment argument stems from Eisner v. Macomber,3 a famous tax case that is generally understood to stand for the realization requirement, or the idea that income cannot be taxed until it is realized by the taxpayer.4 There, the Supreme Court held that a stock dividend paid out from undistributed earnings and profits was not a realization event and therefore not taxable. But the district court in Moore observed that subsequent cases had limited the reach of Macomber. For example, Dougherty v. Commr.5 upheld the Subpart F regime while noting that Macomber did not prevent Congress from looking past the corporate shell to determine taxable income.

There are other provisions of the Internal Revenue Code tax unrealized income, including, but not limited, to the following:

- Certain expatriates must pay an exit tax, calculated as if all of their assets were sold prior to expatriation.

- Some assets are taxed on a mark-to-market system as if they were sold at the end of each tax year, including regulated futures contracts, securities held by dealers, and certain assets held by life insurance companies.

These provisions have survived similar challenges.6

The Moores contended that the tax was not a tax on income – thereby sidestepping the issue of whether the income is realized – but a tax on property. Under this view, the transition tax differs from Subpart F in that Subpart F functions through constructive realization of income, i.e., income realized by a foreign corporation while it is controlled by U.S. shareholders. The Moores distinguished Subpart F from the transition tax by characterizing the latter as a tax levied based on ownership of an asset. The Moores supported their argument with the observation that the tax rates differ depending on the form that the earnings are held in (cash versus other assets). The argument did not convince the district court.

The court was more receptive to the Moores' argument against a retroactive tax. It accepted that the tax was retroactive and dismissed the government's arguments to the contrary, which the court characterized as absurd. But the court was less convinced that this constituted a violation of due process. It cited precedent under U.S. v. Carlton7 that a retroactive tax was constitutionally acceptable if it was supported by a legitimate legislative purpose and furthered by rational means. The court accepted Congress's desire to prevent a windfall on deferred foreign earnings as a legitimate purpose.8 The court further acknowledged that the T.C.J.A.'s move to a territorial tax system represented a large enough change that Congress was justified in taxing earnings dating back to 1986, when the Code underwent its last major revision.

In any case, the district court did not seem to give much weight to the timeframe. It analyzed the other factors in Carlton to determine whether there was a violation of due process:

- The transition tax is not a new tax but rather a modification to Subpart F, which weighed against a finding of due-process violation.

- The transition tax resolved uncertainty by (along with the rest of the T.C.J.A.) making clearer when foreign earnings would be taxed. This also weighed against there being a due-process violation.

- The Moores had had little notice of the transition tax's introduction, which is more suggestive of a due-process violation. But precedent suggested this was not dispositive.

Commenters have disagreed on the amount of notice that the Moores received and should have received. The transition tax was the subject of proposed legislation as early as 2014. But it is not clear that the Moores were the type of taxpayers who could reasonably be expected to pay attention to such developments. The Moores characterized their investment as charitably minded support for their friend and the public good, rather than a sophisticated and profit-oriented business venture. And the shift introduced by the T.C.J.A. was drastic. A C.F.C. that ran an active business would previously not been taxed on its undistributed earnings. The Moores, after learning about and paying the transition tax, sold enough shares to take them below 10% ownership. With more notice, they might have done this sooner.

On the other hand, absence of notice of an upcoming tax change has not been held to be an issue where the increased tax burden "result[s] from carrying out the established policy of taxation."9 Under such broad language, it could be argued that the transition tax expanded on the antideferral policy already established by Subpart F. As U.S. shareholders in a C.F.C., the Moores had an obligation to report information on their ownership in KisanKraft using Form 5471. This might have made them more aware of the broader goal of Subpart F, even if they did not previously have any Subpart F income.

The district court ultimately granted the government's motion to dismiss the case. This result was affirmed by the 9th Circuit. The Supreme Court then granted certiorari.

To view the full article, click here.

Footnotes

1. It appears the Moores' stake fluctuated between 9% and 11% during the relevant time period. "Records Show Moore's Interest in Transition Tax Company Changed." Tax Notes, Oct. 11, 2023.

2. Note that a corporation only needs to meet one of these requirements to be a D.F.I.C.

3. 252 U.S. 189 (1920).

4. The principle in the decision remains in the general rule of Code §305 regarding pro rata stock dividends.

5. 60 T.C. 917 (1973).

6. Some commentators have warned of the collateral effects on these other provisions if the realization requirement is interpreted as the Moores believe. See "If Moore is Reversed." Tax Notes, June 26, 2023.

7. 512 U.S. 26.

8. See participation exemption below.

9. Milliken v. U.S., 283 U.S. 15.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.