On November 15, 2021, President Biden signed into law the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act ("Bipartisan Infrastructure Law" or "BIL"). Vehicle, highway, and crash safety improvements were not a major part of the BIL's... billing. Maybe the lack of publicity on this aspect of the BIL was the result of the legislation's overall vast scope. Whatever the reason, the BIL actually affected (or at least required NHTSA to effect) a number of substantial and consequential vehicle safety initiatives.

It's now just over a year after the BIL's enactment, so I wanted to take this opportunity to discuss the BIL in the vehicle safety context in a two-part series. I'll first discuss what the BIL is—what did it do/require NHTSA to do? In the second part of this series, I'll discuss what NHTSA has done to affect the BIL's mandates in the roughly 14 months since it was enacted.

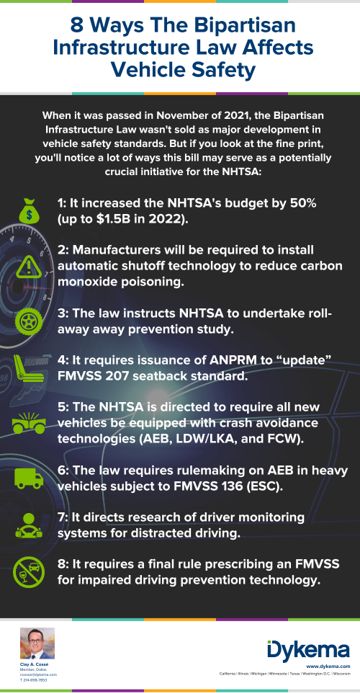

First—what did the BIL do? Here are the major takeaways:

- 50% NHTSA Budget Increase—The BIL increased NHTSA's 2021 budget from $1 billion to $1.5 billion.

- FMVSS 114 CO Poisoning Automatic Shutoff Rulemaking—the BIL requires NHTSA to issue a final rule within two years to amend FMVSS 114 to require keyless internal combustion vehicles to be equipped with automatic shutoff devices "to automatically shut off the motor vehicle after [it] has idled for the period... designated by the Secretary as necessary to prevent, to the maximum extent practicable, carbon monoxide poisoning." This requirement doesn't apply to vehicles with traditional keys or to electric vehicles.

- Roll-Away Prevention Study—the BIL

directed NHTSA to study potential consequences and benefits of

installing roll-away prevention technology in vehicles equipped

with keyless ignition devices andautomatic

transmissions when

- the transmission is not in park;

- the vehicle does not exceed the speed determined by the Secretary to be safe;

- the operator's seatbelt is unbuckled;

- the service brake is not engaged; and

- the door for the operator of the motor vehicle is open.

- FMVSS 207 Update ANPRM—the BIL requires NHTSA to issue an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking ("ANPRM") to "update" the FMVSS 207 seatback standard. If appropriate under the Safety Act, NHTSA is to issue a final rule. The BIL is circumspect here. It requires the ANPRM within two years. But it doesn't provide any guidance on what it means by "update" or what issue or issues any "update" should address. Further, the BIL doesn't address issues like intrusion, override, and child-seat usage, which research and data support are currently more consequential in terms of potential for harm reduction in rear impact crashes than the FMVSS 207 seatback strength requirements.

- Crash Avoidance Rulemaking—the BIL orders NHTSA to promulgate a rule establishing minimum performance standards with respect to crash avoidance technology and requiring all vehicles manufactured for sale after an effective date to be determined by NHTSA to be equipped with Forward Collision Avoidance (FCW) and Automatic Emergency Braking (AEB) and Lane Departure Warning (LDW) and Lane-Keeping Assist (LKA). The BIL also separately requires NHTSA to finalize the 2015 NCAP Request for Comment on advanced crash avoidance technologies. AEB and FCW are by far the most efficacious advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) in terms of crash reduction. Research supports that LDW/LKA provide the next-most benefit. So overall these are logical starting points for ADAS/crash avoidance rulemaking.

- FMVSS 108 Headlamp Rulemaking—NHTSA is directed to issue a final rule including performance-based standards for vehicle headlamps. This is intended to ensure headlights are correctly aimed on the road and to allow for the use of adaptive headlamps. NHTSA actually issued this rule in February 2022.

- Research on Distracted-Driving Monitoring

Systems—within three years of the BIL's

enactment, NHTSA is required to conduct research regarding the

installation and use of driver monitoring systems to "minimize

or eliminate."

- driver distraction;

- driver disengagement;

- automation complacency by drivers; and

- foreseeable misuse of advanced driver-assist systems.

Then NHTSA must, if necessary, initiate rulemaking and if not, report to Congress the reasons for not initiating.

- FMVSS for Impaired Driving Prevention Technology—NHTSA must, within three years of the BIL's enactment, "issue a final rule prescribing a Federal motor vehicle safety standard... that requires passenger motor vehicles manufactured after the effective date of that standard to be equipped with advanced drunk and impaired driving prevention technology." The BIL states that the required compliance date shall be two to three years after the final rule is issued. NHTSA is required to report to Congress if it deems the final rule impracticable or has not finalized it within 10 years of the BIL's passage. NHTSA's charge here includes providing up to $45 million in funding to the Driver Alcohol Detection System for Safety, which I've previously written about.

- Rulemaking on AEB in Heavy Vehicles Subject to FMVSS 136 (ESC)—Under the BIL, NHTSA must within two years prescribe an FMVSS "that requires any commercial motor vehicle [required to have ESC—i.e. truck tractors with GVWR of 26,000 to 29,000 pounds]... to be equipped with [AEB]."

- For a complete summary, see NHTSA's Bipartisan Infrastructure Law wiki.

But briefly, the BIL also directs NHTSA:

- to study child-seat accessibility for low-income families and to provide state funding for child seats for low-income and underserved populations;

- to evaluate new technology and use cases for anthropomorphic test dummies and computer simulations;

- to work towards global harmonization of vehicle regulations;

- to issue a request for comment on hood and bumper standards for crash avoidance, including vulnerable road user safety;

- to study and report on cannabis-impaired driving and counter-measures in states that have legalized cannabis;

- to research crashworthiness in limousines and consider rulemaking accordingly;

- to establish a roadmap for implementation of crash avoidance standards in the New Car Assessment Program;

- to study and require manufacturer reporting on recall completion rates;

- to study state law on and means for prevention of illegal passing of school buses;

- to complete rulemaking on rear underride protection for trailers and semi-trailers;

- to research protection of vulnerable road users; and

- to issue a final rule for unattended occupant detection in vehicles under 10,000 pounds.

The next part of this series will look at NHTSA and Congressional activity in the year since the BIL's passage.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.