INTRODUCTION

If a person thinks one thing but says another, what are others to believe? Statutory interpretation often favors the latter over the former. But within the context of controlled foreign corporations ("C.F.C.'s"), one taxpayer has effectively suggested modifying that paradigm to undo the effects of an unpopular law change.

Altria Group, Inc. ("Altria") is a large U.S. corporation in the business of tobacco, cigarettes, and related products.1 Its other activities include an investment in Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV ("ABI"), a large brewing company that is structured as a Belgian corporation. ABI holds a number of subsidiaries.

The dispute concerns the 2017 tax year, when Altria owned slightly more than 10% of ABI, measured by both vote and value. The balance was held by non-U.S. shareholders. Prior to 2017, certain foreign subsidiaries of ABI would not have been considered C.F.C.'s. However, a change to the ownership attribution rules under the C.F.C. regime changed this result. By reason of the change, the subsidiaries were deemed to be owned by U.S. persons that did not actually own any of the subsidiaries' stock. This caused the foreign entities to become C.F.C.'s, greatly increasing tax compliance burdens for Altria, along with significant penalties for shortfalls in compliance.

Altria filed its 2017 tax return in accordance with the rule change, but it then sued for a refund.2 The basis of its claim is that the 2017 rule change went against the plain reading of the statute as well as Congress's stated intent.

STOCK ATTRIBUTION UNDER C.F.C. RULES

C.F.C.'s in General

In a purely domestic context, U.S. law generally does not tax shareholders on the income of a corporation until the time of distribution. The same rule applied generally to U.S. persons and their foreign corporations. Nonetheless, several antideferral regimes override this principle by requiring certain U.S. shareholders of controlled foreign corporations ("C.F.C.'s") to include some or all of the C.F.C.'s income when and as generated at the level of the C.F.C. A foreign corporation is a C.F.C. if more than 50% of the voting power of all shares of a C.F.C. or more than 50% of the value of all shares outstanding is owned by "U.S. Shareholders." For this purpose, a U.S. Shareholder includes U.S. persons who own shares representing at least 10% of the voting power of all shares of the C.F.C. issued or outstanding or 10% of the value of all shares of the foreign corporation that are issued or outstanding.

Until the T.C.J.A. was enacted in 2017, the policy of Subpart F was to prevent certain intercompany transactions undertaken by a C.F.C. or structures for foreign investment by the C.F.C. to defer income recognition by the U.S. Shareholders of the C.F.C.

Attribution Rules

The 10% and more-than-50% thresholds are measured not just by direct ownership of foreign corporate shares, but also through indirect ownership arising by application of the attribution rules of Code §318. This provision generally attributes stock ownership to persons related to the actual shareholder.

The attribution rules fall under three categories.

- First, an individual shareholder's stock may be attributed to certain family members.

- Second, stock owned by an entity, such as a corporation, may be attributed to the entity's owners. This category of attribution is known as upward attribution.3

- Third, stock in other corporations actually owned by an owner of an entity may be attributed to that entity. This is known as downward attribution. If the entity is a corporation, downward attribution only applies if the shareholder holds at least 50% of the corporation. But if this threshold is met, all stock held by the shareholder is attributed to the corporation, rather than downward attribution to the to the shareholder's ownership percentage in the corporation. For example, if a shareholder holds 50% of a corporation, then the corporation is deemed to hold all other stock held by the shareholder rather than 50% of the stock in another corporation.

In some, but not all, instances, these rules can apply multiple times. If a person is deemed to own stock via attribution, the stock can be attributed again to another person. Suppose a shareholder of a corporation is deemed to own the stock of the corporation's subsidiary. The subsidiary stock can be further attributed to the shareholder's family members.

The C.F.C. rules import the attribution rules found in Code §318, with some modifications. The modification at the heart of the Altria case concerns downward attribution. Prior to the effective date of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (the "T.C.J.A,"), Code §958(b)(4) turned off downward attribution if the effect was that a U.S. person would be attributed stock from a non-U.S. person. This provision was repealed by the T.C.J.A.

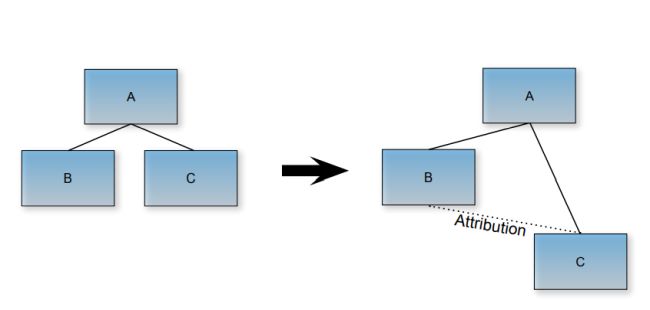

The following diagram shows a standard application of downward attribution. B, being a corporation owned by A, is deemed to own other stock held by A (namely, stock in C).4

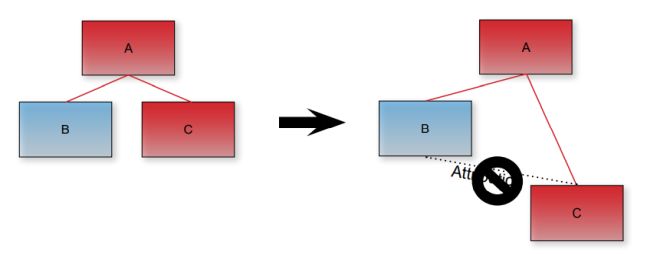

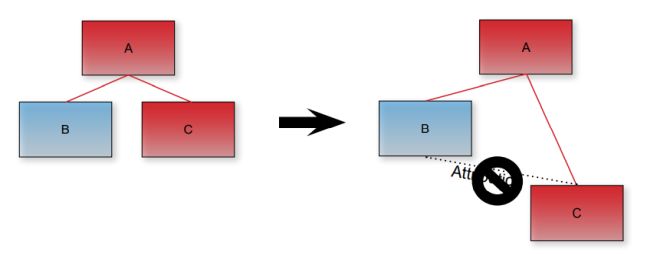

Now suppose A is a foreign corporation. Prior to the effective date of the T.C.J.A., Code §958(b)(4) barred downward attribution from a foreign person to a U.S. person for purposes of the C.F.C. rules. If A were a foreign corporation, B would not have been deemed to own other stock held by A.

This is no longer the case with the repeal of that provision.

APPLICATION TO ALTRIA

The following diagram shows, in relevant part, the structure of Altria vis-à-vis ABI.

Altria directly held 10.2% of ABI. Through the application of the indirect ownership rules and constructive ownership, Altria was also deemed to hold 10.2% of each of the foreign ABI subsidiaries. ABI directly or indirectly wholly owned each subsidiary, and Altria was considered to hold its proportionate 10.2% share of ABI's 100% ownership. The result was that while Altria was a U.S. Shareholder with respect to all foreign entities, total U.S. ownership did not exceed 50% for ABI Subs 2 and 3. The only C.F.C. was ABI Sub 1, as it was majority-owned by ABI US, a U.S. person.

The analysis became more complicated with the T.C.J.A. With downward attribution now freely applicable, ABI US was deemed to own the stock held by its parent, ABI. Therefore, ABI US actually and constructively held all of the shares of ABI Subs 1, 2, and 3. With the latter two subsidiaries, ABI US's ownership was entirely constructive, as it did not directly hold shares in either subsidiary.

Because a U.S. person (ABI US) was now considered to hold more than 50% of Subs 2 and 3, each subsidiary became a C.F.C. And since Altria was already a U.S. Shareholder with respect to those subsidiaries, their change to C.F.C. status meant that Altria would have to include, on a current basis, its proportionate share of the subsidiaries' income as of 2018 and onward.5

Altria's Arguments

Altria's claim for a refund rests on two main arguments. First, it believes that treating Subs 2 and 3 as C.F.C.'s violates the plain-language definition of a C.F.C. that appears in Code §957. This is in spite of the fact that Code §957's plain language requires, via Code §958(b), the incorporation of Code §318's attribution rules. To get around this issue, Altria cites Treasury comments from the 1960's, when the C.F.C. regime was first enacted, to define the term "control." Those comments indicate that control is a concern because control would mean U.S. shareholders have effectively already realized the income earned by C.F.C.'s.:

Congress has the power under the 16th Amendment to impose a tax on undistributed earnings of a foreign corporation controlled by U.S. shareholders on the ground that it may find that such income is constructively received by the U.S. shareholder * * *.6

The legislative history adds that the 10% threshold for counting U.S. Shareholders is important because control exists when it is concentrated in a relatively limited number of U.S. shareholders. Altria underlines that this is not true in "situations where ownership was widely scattered, and no U.S. group was in effective control."7

Plainly, neither Altria nor ABI US effectively control ABI or Subs 2 and 3. Consistent with this argument, Altria's complaint emphasizes that it has little influence on ABI's governance.

Second, Altria cites legislative history relating to the repeal of Code §958(b)(4) to point out that situations like Altria's were not meant to be captured by the repeal. The repeal was aimed at situations where a foreign-owned U.S. corporation with a foreign subsidiary could decontrol the foreign corporation through asset-stuffing transactions between the ultimate foreign parent of the U.S. corporation and the foreign subsidiary. Attribution to the U.S. corporation would have been barred under Code §958(b)(4), allowing the group to "convert[ ] former CFCs to non-CFCs, despite continuous ownership by U.S. shareholders."8

Outside that fact pattern, it seems Congress intended for Code §958(b)(4) to remain in place:

This provision is not intended to cause a foreign corporation to be treated as a controlled foreign corporation with respect to a U.S. shareholder as a result of attribution of ownership under section 318(a)(3) to a U.S. person that is not a related person (within the meaning of section 954(d)(3)) to such U.S. shareholder as a result of the repeal of section 958(b)(4).9

In fact, the Senate considered amending the T.C.J.A. to explicitly limit the scope of the change, but it appears that the Senate decided it was unnecessary according to Orrin Hatch, the then-chairman of the Senate Finance Committee:

The conference report language for the bill does not change or modify the intended scope [of the above statement]. The Treasury Department and the Internal Revenue Service should interpret the stock attribution rules consistent with this explanation, as released by the Senate Budget Committee. I would also note that the reason [the] amendment No. 1666 was not adopted is because it was not needed to reflect the intent of the Senate Finance Committee or the conferees for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.10

In other words, the complete repeal of Code §958(b)(4) may have been a result of a misunderstanding. Altria's evidence makes clear that at some point, the Treasury Department overstepped the intended scope of the 2017 change in law.

With both arguments, Altria believes an understanding of congressional intent is required to apply the rules as intended by Congress. That would seem contrary to typical practice, where congressional intent is brought in if rules are unclear or contradictory. For example, the Supreme Court stated that legislative history "need not be consulted when...the statutory text is unambiguous."11 Here, while the rules may have unintended consequences and be substantively inequitable, the mechanics are clear. The idea that congressional intent may be insufficient to modify application of the post-T.C.J.A. law is underlined by the number of proposals from legislators and commentators to remedy the situation.

CONCLUSION

Many commentators agree with Altria's characterization of the repeal as "absurd."12 But whether Altria's desired method for undoing the absurdity will succeed is uncertain. For the moment, Altria has petitioned the court to stay proceedings until Moore, another prominent lawsuit regarding C.F.C.'s that is currently before the Supreme Court, is decided. The C.F.C. regime may see several significant changes in the near future.

Footnotes

1. The business is perhaps better known as Philip Morris, its originator, predecessor, and affiliate.

2. Altria Group, Inc. v. U.S, (E.D. Virginia, Docket No. 3:23-CV-00293).

3. If the entity is a foreign entity, a slightly different set of rules apply under Code §958(a)(2).

4. Note that in parallel, C is deemed to own stock of B.

5. Note that while ABI US's constructive ownership caused Subs 2 and 3 to become C.F.C.'s, constructive ownership does not apply for purposes of income inclusion. Therefore, ABI US was not required to include C.F.C. income from Subs 2 and 3. However, constructive ownership is distinguished from indirect ownership through foreign entities, which applies for purposes of income inclusion. Consequently, Altria was required to include its share of the income of Subs 2 and 3.

6. President's 1961 Tax Recommendations: Hearings Before the H. Comm, on Ways & Means, 87th Cong., 1st Sess.

7. S. Comm. on Finance, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. (1962) (emphasis added by Altria).

8. H.R. Rep. No. 115-409, at 387 (2017); H.R. Rep. No. 115-466, at 507-508 (2017).

9. S. Comm, on Budget, Reconciliation Recommendations Pursuant to H. Con. Res. 71, S. Rep. No. 115-20, at 383 (2017) (emphasis added by Altria).

10. 163 Cong. Rec. S8, 110 (2017).

11. U.S. v. Woods, 571 U.S. 31 (2013).

12. Citing KMart Corp. v. Cartier, Inc., 486 U.S. 281 (1988) ("[It is a] venerable principle that a law will not be interpreted to produce absurd results.").

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.