Nigeria is preparing for a change of government in May even though opposition parties are still challenging the outcome of last month's presidential election in court (see our note on the election). Bola Tinubu and the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) will have a smaller majority in parliament – assuming he is affirmed as the rightful president-elect. However, the opposition will be fragmented and serious threats to the legislative agenda are more likely to arise from potential instability in the ruling party.

Significance – Ethnic politics

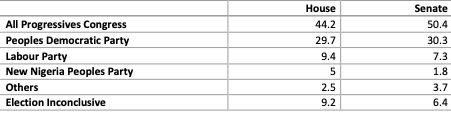

Last month, the APC won 44% of seats in the House of Representatives and about half of Senate seats. Comparatively, its share of seats in the House was 58% four years ago. This decline illustrates the fall in APC's popularity since it first came to power in 2015.

The rise of two smaller parties in the current cycle further tilts the balance of power in the incoming parliament, at least on paper. Peter Obi's Labour Party (LP) and Rabiu Kwankwaso's New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP) have won about 10% of seats combined in the bicameral legislature, meaning they can challenge the ruling party if they cooperate with the bigger Peoples Democratic Party. However, ethnic rivalries (e.g., between Hausa and Igbo) stand in the way of that cooperation here.

The NNPP's lawmakers in the National Assembly will mostly come from Kano, which is a predominantly Hausa state. On the other hand, most LP lawmakers will be from a part of the south where Igbo is the largest ethnic group. An aborted alliance between both parties before last month's presidential election typifies the rivalry between both ethnic groups.

In terms of alliances, the LP is more inclined to act in concert with the People's Democratic Party (PDP) given their previous relationship and shared support base. The LP's 2023 presidential candidate Obi was the running mate to the PDP's Atiku Abubakar in the 2019 election, and the southern areas that the LP will now represent in parliament were historically represented by the PDP. Similarly, the NNPP's natural ally is the APC because it dislodged the APC in Kano this year and they have a shared support base.1

Meanwhile, the APC will continue to govern under a spoils system where infighting over the distribution of power can hinder policy execution. For example, disputes over political spoils after the 2015 elections slowed legislation, weakened government effectiveness and dented relations between the executive and the legislature. Now, a fresh round of disputes seems imminent over how the APC should allocate roles, such as Senate president and House speaker, among ethnic groups.

Outlook – Legislative business

Partisan and ethnic interests will sometimes converge in the incoming government, but opposition parties in parliament are unlikely to collaborate with each other effectively due to ethnic differences. Any friction in the legislative process will depend on competition between ethnic groups for patronage under the new administration, and for leverage ahead of the 2027 presidential election when the two leaders of NNPP and LP will look to contest against each other again. In this context, simmering tensions in the ruling party will be the chief source of risk to legislative business and not the fragmented opposition.

Footnote

1. Kano is Nigeria's most populous state. Formerly an APC stronghold, the state will now have an NNPP governor and most of its representatives in the new National Assembly will be NNPP.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.