Here we are with the second chapter of this short essay on the most common pitfalls related to patents which ran across during our activity as consultants; as in the first chapter, we will list the pitfalls and try to provide some indications and food for thought to try to avoid them or at least limit their consequences.

B1) Confusing patentability with freedom to operate

Many people think that if they obtain a patent on a certain technical solution, they can freely use that technical solution.

A patent gives the applicant an exclusive monopoly on a certain technical solution, therefore the right to prevent third parties from using it or profiting from it, but it does not guarantee that that technical solution will not interfere with third party patents.

We will try to better explain this concept with the following example.

Let's imagine we invented a pencil with an incorporated eraser (hence assuming hypothetically that the pencil with the incorporated eraser is new and inventive) and we obtained a patent X on it.

As we tried to schematize in the previous figure, the patent X constitutes a sort of fence around our technical solution, and therefore no one, without our authorization, is allowed to produce, commercialize, or use any pencil with an incorporated eraser.

The question is now whether we can use a pencil with the incorporated eraser.

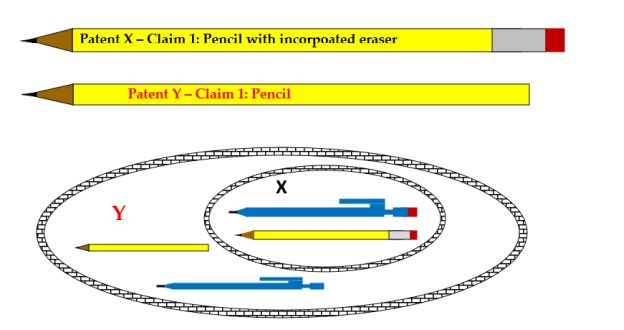

If a second subject had filed and obtained before us a patent Y which protects a pencil in itself (in this case, too, we will assume that the pencil was new and inventive at the time in which patent Y was filed), he/she would have obtained a monopoly (therefore a wider fence than that of the patent X) on this technical solution.

In this specific case, we will not be able to use the pencil with the incorporated eraser because it is still a pencil, so it would fall within the scope of protection of the patent Y.

As we tried to illustrate, therefore, the grant of a patent X does not automatically imply that its holder can use the technology that he has patented, as there could exist a previous and still active patent Y that protects a more general concept and that must be applied in order to use the solution X; in this situation, patent X is a "dependent" patent with respect to patent Y.

However, it is important to point out that likewise the owner of patent Y cannot use the pencil with the incorporated eraser, as if he does so, it will fall within the scope of protection of patent X.

In this case, a so-called cross license could be taken into consideration by the parties: the patent holder X grants the patent holder Y the use of the pencil with the incorporated eraser, and the patent holder Y authorizes the patent holder X to use the pencil.

B2) A granted patent does not mean that it is unassailable

A patent is valid until proven otherwise, and it is always possible to take steps before a national court to try to demonstrate its nullity.

Typically, the validity of a patent is challenged by producing either patent documentation (i.e. earlier patents) or a different documentation (i.e. pre-disclosure evidence such as dated brochures, sales invoices, evidence, etc.), which aim at demonstrating that the subject matter of the patent was already known before the filing date of the same.

It is very frequent that the outcome of a nullity action by a court is a declaration of nullity or a limitation of the protection of the patent.

Some legislations (for example the European Patent Office and the USA ones) also provide, for a certain period of time after the grant of the patent, a procedure called "opposition", thanks to which third parties can produce – before a patent office (and therefore not before the court, which can always be done anyway) –documentation and the argumentation against the validity of the patent in question.

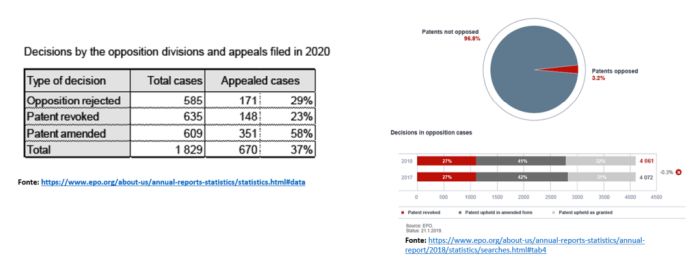

You will find below the official data published by the European Patent Office concerning the oppositions filed before the same in 2020.

As shown in the chart, in 2020 less than a third of the oppositions ended with the maintenance of the patent as initially granted (opposition rejected), more than a third of the oppositions ended with the cancellation of the patent (patent revoked) and around a third of oppositions ended with the maintenance of the patent with a modified and necessarily limited protection (patent amended) compared to the originally granted version.

It is therefore clear that the granting of a patent does not necessarily mean that it cannot be invalidated before a patent office (if and when possible) or before a national court.

B3) Deeming a patent invalid because it seems trivial at first sight

Nevertheless, it is not legitimate to consider a patent invalid just because the invention, object of it, seems trivial.

A granted patent is considered valid until proven otherwise, and the holder of it can therefore sue the alleged infringer, who will have then to demonstrate to the judge that the patent is not valid.

To revoke a patent, public and proven documents are needed, and the local legislation regarding novelty and inventive activity must be considered.

To prove pre-use or pre-disclosure, all steps must be certain and documented; for example (but not only) sales invoices must bear the code of a machine, then the same code must be present in the dated drawings of the machine and in the plate of a machine which has been available on the market before the filing date of the patent to be revoked, and preferably there should be a statement of the person from whom the machine is being withdrawn, etc.

In the face of a high level of initial enthusiasm for a possible pre-disclosure, it often happens that then it is not possible to reconstruct a continuous and effective chain of evidence of the pre-disclosure, for example because after many years it is no more possible to find a sample of a machine sold with the requested characteristics, or simply because the codes shown in the invoice or in the transport document do not correspond to the codes present on the drawing or on the machine plate because of a change which had been made to the management system. For all these reasons and others more, it may not be possible to provide an unequivocal proof of pre-disclosure.

Therefore, a granted patent must always be considered valid, at least until an unequivocal proof of its nullity is made available.

B4) Not keeping historical records

To prove a pre-disclosure (i.e. in an opposition or lawsuit), it can be very helpful to keep the documentation proving the pre-disclosure in question, such as catalogues, samples, material for trade fairs, etc.

To this end and within reason, it could be useful to buy and keep your products on the market together with their proofs of sale (invoices, delivery notes, etc.), the first time a new product is placed on the market, in order to preserve evidence of pre-disclosure in the case in which, years later, someone tries to patent the same solution (maybe without even knowing about the pre-disclosure).

Keeping historical documentation can also be useful to avoid searches for new patents on already known but old solutions, which might otherwise be forgotten.

We await you soon for the third and final chapter.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.