Originally published in the National Venture Capital Association and Ernst & Young LLP publication, Venture Capital Review, Issue 17, Spring 2006.

For a number of years, many private equity funds have had the ability under their partnership agreements to create "alternative investment vehicles" (AIVs) to facilitate one or more specific investments. Typically, a fund is permitted to establish an AIV to accommodate the "tax, legal or regulatory" concerns of any partner or the partnership as a whole.

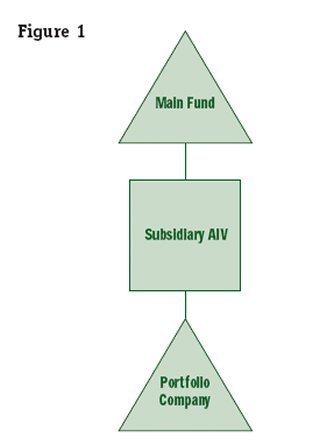

There are two broad categories of AIVs. The first type, often referred to as a "subsidiary AIV," is owned directly by the fund (either in whole or in part with other investors). The subsidiary AIV in turn holds the portfolio investment. See Figure 1.

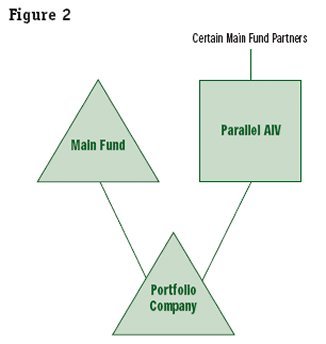

The second kind of AIV, usually called a "parallel AIV," is not owned by the fund, but rather by a subset of the fund’s partners, including the general partner. The parallel AIV invests in the portfolio company alongside the fund, which also holds a direct investment in the portfolio company. See Figure 2.

Parallel AIVs are distinguished from "parallel funds"— which also may be established to satisfy tax, legal or regulatory concerns—in that parallel funds are designed to make multiple investments alongside the fund. In fact, parallel funds typically are required to invest pro rata in all fund investments, except as necessary to satisfy the tax, legal or regulatory purpose for which the parallel fund was established. A parallel AIV, on the other hand, is designed to invest in a single portfolio company.

A fund’s partnership agreement typically requires that the terms and conditions applicable to the AIV must be "substantially the same" as the terms and conditions of the fund’s partnership agreement, except as necessary to satisfy the tax, legal or regulatory purpose for which the AIV was created. The fund’s partnership agreement may also require that the economics of both the AIV and the fund—including the management fee, allocations, distributions and the general partner’s clawback—must be coordinated and, if necessary, adjusted to carry out the overall economic arrangement of the parties.

Subsidiary AIVs are commonly used. For example, funds often invest through a subsidiary AIV domiciled in a non-U.S. jurisdiction to take advantage of a tax treaty—such as making Canadian investments through a Barbados entity or investing in India through a Mauritius company. Funds also use subsidiary AIVs to invest in operating LLCs (or partnerships)1 to address investor concerns regarding "unrelated business taxable income" (UBTI) and "effectively connected income" (ECI). (This structure is discussed in more detail below.)

Parallel AIVs, on the other hand, were used much less frequently until recently. One reason for this, discussed further below, is that parallel AIVs (as opposed to subsidiary AIVs) may raise additional tax issues for tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors. Another reason is that parallel AIVs, which require investment "opt outs" at the fund level, can create difficult economic adjustments to achieve the intended overall economic deal.

Recently, however, a number of buyout funds have begun to use parallel AIVs to address tax concerns of their investors. While it is unclear whether this practice will spread to the venture capital industry, some venture funds recently have updated their partnership agreement tax provisions in order to take advantage of parallel AIVs.

This article discusses the tax purpose and structure of parallel AIVs created to deal with UBTI/ECI issues arising from investments in flow-through operating companies and also highlights some of the economic and tax issues that may arise as a result.2

UBTI and ECI

Many funds are required under their partnership agreements to minimize the incurrence of UBTI and ECI. Even funds without such contractual restrictions (or funds that explicitly can invest a specified portion of their capital commitments in UBTI- or ECI-generating investments) often will attempt to minimize UBTI and ECI in recognition of the negative impact on their tax-exempt and non-U.S. limited partners.

UBTI affects tax-exempt investors, while ECI affects non-U.S. investors. These two types of income are similar, and both can arise when a fund invests directly into an operating company that is treated as a flow-through entity for U.S. federal income tax purposes (i.e., an operating LLC or partnership). UBTI also may arise as a result of borrowing by a fund. ECI, on the other hand, also can result from a fund’s investment in U.S. real property or in a corporation that owns a certain amount of U.S. real property.

Tax-exempt investors generally do not pay U.S. federal income tax other than with respect to income that is UBTI—which is income from a trade or business that is unrelated to the investor’s tax-exempt purpose.3 The Internal Revenue Code (the Code) imposes tax on UBTI at the same rates applicable to U.S. trusts or corporations, currently at a maximum rate of 35%.4 Interest, dividends and capital gains, however, are generally excluded from the definition of UBTI.5

Accordingly, the investment activities of a typical venture capital fund—which largely generate interest income and capital gains—will not give rise to UBTI, unless the fund borrows or invests directly in an operating LLC. The Code imputes the unrelated trade or business activities of a partnership to its partners.6 Therefore, the business activities of an operating LLC are imputed to any fund that directly holds equity in that operating entity, and that business activity in turn is imputed to the fund’s tax-exempt partners. In addition to the payment of tax on UBTI, tax-exempt investors must file a U.S. federal income tax return, reporting UBTI, if their gross income included in the computation of UBTI equals or exceeds $1,000.7 They may also be required to file state income tax returns in those states in which an operating LLC has activities.

Like tax-exempt investors, non-U.S. investors generally do not pay net U.S. federal income tax on interest, dividends or capital gains.8 Unless a tax treaty applies, however, a non-U.S. investor will bear U.S. withholding taxes on dividends and certain types of interest income (currently at a 30% rate).9 Capital gains, however, that are earned by non-U.S. investors generally are not taxed at all in the U.S., unless the gains are attributable to U.S. real property.10

Nevertheless, non-U.S. investors are required to pay U.S. federal income tax on all ECI—income that is "effectively connected" with the conduct of a U.S. trade or business—regardless of whether that income otherwise would be interest, dividends or capital gains.11 ECI is taxed at the same rates applicable to U.S. individuals, trusts or corporations (currently at a maximum rate of 35%). Non-U.S. investors engaged in a U.S. trade or business must also file a U.S. federal, and possibly state, income tax returns.12

As is the case with UBTI, the typical activities of a venture capital fund—investing in corporate stock and other securities—generally should not constitute a U.S. trade or business for this purpose, unless the fund invests in U.S. real property (or a corporation that owns a certain amount of U.S. real property) or invests directly in an operating LLC. Like UBTI, the U.S. trade or business of an operating LLC is imputed to any fund directly holding equity interests in that operating entity, and that U.S. trade or business in turn is imputed to the fund’s non-U.S. partners.

In addition to the regular U.S. federal income tax on ECI, a non-U.S. investor that is a corporate entity may be subject to a U.S. "branch profits" tax on its ECI. This tax is intended to replicate the withholding tax that would apply to a domestic corporation paying dividends to non-U.S. shareholders. Unless reduced by a tax treaty, the branch profits tax currently is imposed at a 30% rate on the foreign corporation’s ECI that is net of the regular U.S. federal income tax and is deemed repatriated to that corporation.13 As a result, the effective U.S. federal income tax rate on ECI earned by foreign corporations may equal up to 54.5%.

Tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors wish to avoid UBTI and ECI, respectively, for two reasons. First, they do not want their investment returns to be subject to U.S. federal income tax. Historically most private equity and venture capital funds have been able to achieve this result for their tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors.

Second, these investors want to avoid filing U.S. federal and state income tax returns. This goal has become less important in recent years to a number of tax-exempt investors, many of whom have begun to file returns and report UBTI in connection with varied activities and investments, but state tax returns might still be an undesired burden. U.S. return filing, however, remains of paramount importance to many non-U.S. investors, far outweighing the burden of indirectly paying U.S. federal income tax. In addition, some tax-exempt investors still prefer to minimize the amount of UBTI that they must report to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), even if it means indirectly bearing more U.S. tax, to avoid the possibility of jeopardizing their tax-exempt status. And, of course, there are certain tax-exempt investors who have never reported UBTI and who, for various reasons, do not wish to report any in the future.

With respect to these two goals—minimizing U.S. federal income tax and not filing U.S. income tax returns— parallel AIVs address only the tax return filing concern, and as discussed below, they may not completely resolve this issue for non-U.S. investors.

Purpose of Parallel AIVs

As mentioned above, buyout funds increasingly have been using parallel AIVs in conjunction with invest- ments in operating LLCs to address the UBTI and ECI tax return filing concerns of their investors. Parallel AIVs, however, do not prevent tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors from indirectly bearing U.S. federal income tax. In fact, the indirect tax burden may be greater because of the U.S. "branch profits" tax.

Parallel AIVs also do not prevent the fund itself from being engaged in the U.S. trade or business of the operating LLC into which the fund and its parallel AIV invest. Parallel AIVs, therefore, generally will not satisfy the contractual undertakings in typical partnership agreements regarding UBTI and ECI—which usually require the general partner to use a specified level of effort (e.g., "commercially reasonable efforts" or "best efforts") to avoid causing the fund from being engaged in a trade or business and to avoid generating UBTI and ECI. Partnership agreements, however, can be specifically tailored to provide that the UBTI and ECI undertakings are deemed to have been satisfied if the general partner has offered parallel AIVs to the tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors (whether or not those investors choose to participate in the parallel AIV). A number of buyout fund agreements contain this specific parallel AIV tax language, and some venture capital funds have updated their partnership agreements to add this language as well.

The parallel AIV tax structure is relatively simple. Prior to making an investment in an operating LLC, funds typically will offer their tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors the option of contributing capital for the investment directly to a parallel AIV. The parallel AIV is established as an offshore entity, treated as a corporation for U.S. tax purposes, in a tax-neutral jurisdiction, such as the Cayman Islands, to avoid local taxation. The main fund invests directly in the operating LLC, but those limited partners who have elected to participate through the parallel AIV "opt out" of the investment through the main fund. The parallel AIV also acquires an equity interest in the operating LLC, typically investing pro rata with the main fund based upon respective commitments.

Any UBTI or ECI allocated by the operating LLC to the parallel AIV is "blocked" as a result of the parallel AIV being treated as a corporation for U.S. tax purposes.

The parallel AIV (as a non-U.S. person) must pay U.S. federal income tax on the ECI allocated to it by the operating LLC, currently at a maximum rate of 35%. Prior to the year in which the operating LLC investment is liquidated, the parallel AIV may also be subject to the branch profits tax on its after-tax ECI, creating an overall rate of U.S. federal income tax of up to 54.5%. Tax-exempt and non-corporate, foreign investors who invest through the main fund, rather than the parallel AIV, would not be subject to the branch profits tax, and therefore would have borne U.S. federal income tax at a maximum rate of 35%. As a result, the indirect tax cost to those investors could be greater as a result of participating in the parallel AIV.14

Upon liquidation of the operating LLC investment, any resulting gains generally would be taxable as ECI, but the parallel AIV may be able to avoid the branch profits tax with respect to such gains because its U.S. trade or business should terminate for U.S. tax purposes immediately after the disposition.15 For this reason, among others, a separate parallel AIV should be created for each operating LLC investment. Accordingly, if the gain from an investment is expected to occur largely upon exit, with little or no operating income during the life of the investment, then the branch profits tax cost may be minimal.

The parallel AIV also will be required to file a U.S. federal income tax return, but its investors should not be required to file a return, solely as a result of their participation in the parallel AIV. Whether those investors may nevertheless be required to file a U.S. tax return as a result of being limited partners in the main fund, even though they have "opted out" of the main fund’s investment in the operating LLC, is discussed below.

In the parallel AIV structure, the main fund invests directly into the operating LLC, and those limited partners who have elected to participate through the parallel AIV opt out of their share of the main fund’s direct investment. Accordingly, the fund’s partnership agreement should have opt out mechanics so that the allocations, distributions and other economic provisions give effect to the fact that some investors are participating only through the parallel AIV. In particular, the allocation provisions of the fund’s partnership agreement should work to specially allocate any income from the operating LLC, which generally will constitute UBTI and ECI, only to those partners who did not participate in the parallel AIV.16 The opt-out mechanics may require numerous adjustments over the life of the main fund, because the profits and losses of the fund are ultimately calculated on an aggregate, not deal-bydeal, basis. For example, if there are aggregate losses in the main fund and a gain in a parallel AIV (or vice versa), special adjustments must be made. Accordingly, depending upon the timing of the fund’s cash flows, it may be impossible to implement the opt out perfectly.

Contrasted with Subsidiary AIVs

Although buyout funds have begun to use parallel AIVs more frequently, many funds traditionally have used subsidiary AIVs to deal with the UBTI/ECI issue of investing in an operating LLC.17 In its most basic form, the subsidiary AIV structure consists of a fund investing into the operating LLC through a wholly-owned, U.S. blocker corporation. Any current income generated by the operating LLC would be taxable to the subsidiary AIV at the U.S. federal corporate income tax rate (currently a 35% maximum rate). In addition, any gains from the sale of the operating LLC would be subject to corporate-level tax (and additional withholding tax on amounts distributable to non-U.S. partners). This latter tax might be avoided if the fund converts the operating LLC into a corporation prior to exit. Such tax also could be avoided if the acquirer purchased the fund’s interest in the subsidiary AIV. Typically, however, a buyer prefers to acquire the operating LLC interests directly in order to obtain a step up in the tax basis of the LLC’s assets, which can then be amortized for tax purposes.

Although the subsidiary AIV protects the fund’s taxexempt and non-U.S. partners from directly incurring UBTI and ECI, respectively, and having to file U.S. income tax returns, the structure is tax inefficient because all partners of the fund, including the general partner, indirectly bear a corporate-level tax even though they may be indifferent to the characterization of income as UBTI or ECI.

Not surprisingly, there are a number of variations to the basic subsidiary AIV structure, all with the goal of reducing the subsidiary AIV’s corporate-level tax. These features include capitalizing the subsidiary AIV partly with debt in order to generate interest deductions or having the fund hold an option to acquire interests in the operating LLC from the subsidiary AIV. Despite these features (which create tax risk largely depending upon the degree to which they reduce corporate-level tax), some corporate-level tax slippage will result from the subsidiary AIV structure, unless the operating LLC generates no current income and the fund is able to sell its interests in the subsidiary AIV.

In contrast, the parallel AIV structure creates no corporate- level tax burden for those limited partners who

choose to invest directly through the main fund. To avoid a corporate-level tax with respect to the general

partner’s carried interest that is attributable to the parallel AIV’s gains, a subsidiary partnership typically is

used. In this structure, the parallel AIV invests into the operating LLC through a newly created subsidiary

partnership, in which the general partner is also a partner.

See Figure 3.

The general partner receives its carried interest attributable to the parallel AIV’s gains through the sub-partnership, rather than directly from the parallel AIV. As a result, the general partner receives its carried interest without bearing any corporate-level tax. If the subsidiary partnership is not used, the general partner’s share of any gains realized by the parallel AIV will be subject to corporate-level taxation (and possibly the branch profits tax). Rather than use the subsidiary partnership structure, some funds simply require the limited partners participating in the parallel AIV to bear the general partner’s share of the corporate-level tax by "grossing up" the general partner’s carried interest to a pre-tax amount.

Tax Return Filing Issue

While parallel AIVs are much better from a U.S. tax perspective than subsidiary AIVs for those U.S. partners (including the general partner) who are indifferent to UBTI and ECI, the question remains whether parallel AIVs adequately address the goal of preventing tax return filings.

Tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors should not have to file a tax return solely as a result of their participation in a parallel AIV. Although there are several theoretical grounds upon which the IRS could attempt to disregard the parallel AIV, those arguments are relatively weak based upon existing authority.18 Perhaps more importantly, the IRS has little incentive to disregard the parallel AIV since the amount of U.S. federal income tax due as a result of the parallel AIV generally is equal to or greater than the tax attributable to a direct investment.

Nevertheless, the issue remains whether the parallel AIV investors are required to file a U.S. federal income tax return simply as a result of being limited partners in the main fund, which has invested directly in the operating LLC.

Assuming that the main fund’s partnership agreement is drafted properly to accommodate the opt outs by the parallel AIV investors, the special allocations of UBTI and ECI away from such investors should be respected for U.S. tax purposes. As a result, tax-exempt investors should not have to report UBTI as a result of their investment in the main fund.

Non-U.S. investors, however, are required to file a U.S. federal income tax return if they are engaged in a U.S. trade or business, regardless of whether they are allocated any ECI.19 As discussed above, the U.S. trade or business of the operating LLC is imputed to the fund and its partners, whether or not they participate in that investment. Accordingly, non-U.S. investors are technically required to file a U.S. federal income tax return even though they have opted out of the main fund’s investment in the operating LLC and have participated in that investment only through the parallel AIV.

What are the consequences to non-U.S. investors if they fail to file a U.S. tax return, even though they have not received any ECI and therefore do not owe any U.S. federal income tax?

Currently, there generally is no explicit penalty for failing to file a return under these circumstances because most "failure to file" penalties are based upon the amount of tax due. Nevertheless, the Code provides that a non-U.S. person may claim deductions or credits against its gross ECI only if it has filed a "true and accurate" tax return, including all information that the IRS determines is necessary for the calculation of such deductions and credits.20 Accordingly, if a non-U.S. person has no gross ECI with respect to a tax year in which no tax return is filed, then the ability to take U.S. deductions or credits with respect to such year should not matter. However, if it later turns out that such non- U.S. person actually earned gross ECI during that tax year, then such person would be subject to U.S. federal income tax (and interest and penalties) on that gross ECI, without the ability to take related deductions or credits attributable to that tax year.

The question that arises is whether a U.S. tax return can be filed late, after the non-U.S. person realizes that a mistake was made and that it actually had earned gross ECI during such year. The answer seemed relatively straightforward, until quite recently. Treasury Regulations stipulated that a tax return had to be filed by a non-U.S. corporation within 18 months and by a non-U.S. individual within 16 months after its original due date in order for that non-U.S. person to take deductions or credits against its gross ECI with respect to such year.21

On January 26, 2006, however, the Tax Court struck down the 18-month deadline for non-U.S. corporations, holding that the IRS had exceeded its regulatory authority by issuing a regulation that was contrary to the plain meaning of the Code, which according to the Tax Court contained no time element.22 As a result of the Swallows Holdings decision and based upon prior case law, a non-U.S. corporation apparently may now file a U.S. tax return (and take ECI-related deductions) at any time before the IRS issues a notice of deficiency or files a substitute return with respect to the tax year in question.23 Depending upon when the IRS issues a notice of deficiency (or files a substitute return), the taxpayer might have more or less time than the 18- month deadline contained in the Treasury Regulations. At this point, it is unclear whether the IRS will appeal the Tax Court’s decision, which some tax commentators have criticized as an incorrect holding by the Tax Court. It is also unclear whether the 16-month filing deadline for non-U.S. individuals, which is contained in a parallel regulation that was not explicitly addressed in Swallows Holdings, continues to apply.

Accordingly, a non-U.S. investor who is confident that it does not have gross ECI in a given tax year generally can ignore the U.S. federal income tax filing requirement without penalty. Nevertheless, if it turns out that such non-U.S. investor actually had gross ECI during such year, it will be subject to U.S. federal income tax on that gross ECI, unless it manages to file a U.S. tax return prior to receiving an IRS notice of deficiency (or perhaps prior to the 16-month deadline, in the case of a non-U.S. individual).

Excess Business Holdings

Although tax-exempt investors should not have to report UBTI as a result of a parallel AIV investment, private foundation investors should be careful to avoid having an "excess business holdings." The Code generally imposes excise taxes on private foundations that have more than a 20% interest in any "business enterprise."24 Whether a parallel AIV would be treated as a business enterprise for this purpose depends on the type of income that it receives, but it is certainly possible that a parallel AIV that holds an interest in an operating LLC would be treated as a business enterprise.

As a result, private foundation investors should make sure that the excess business holdings withdrawal language in the fund’s partnership agreement (or in their side letters) applies to any parallel AIV as well as the fund itself. Private foundations that invest in a fund without such contractual protections (and instead rely on the fact that they own less than 20% of the fund) should be careful because they could end up owning more than 20% of a parallel AIV established by the fund, particularly if the fund has few tax-exempt or non-U.S. investors.

Why the Rise in Parallel AIVs?

Since the ability to use parallel AIVs has been around for years, why have buyout funds begun to use them in the last few years and why have venture capital funds begun to include the use of parallel AIVs to satisfy their UBTI and ECI undertakings?

One reason is that operating LLCs have become more common in the U.S. within the last several years, and their founders also are more likely to resist converting them into corporations, because the founders themselves receive tax benefits as a result of the company’s pass-through tax treatment. Also, funds have focused on the fact that buyers are willing to pay more for operating LLCs (because of the tax benefit to buyers from the asset basis step up), and so, to maximize their overall returns, funds have an additional incentive to structure around the UBTI and ECI consequences to their investors.

Another reason is that "good" deal flow has become more difficult, and therefore fund sponsors need to make economically attractive investments, even if it means that their tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors might bear an additional U.S. tax cost—particularly if such investments represent only a fraction of the fund’s entire investment portfolio (e.g., less than 25% of aggregate capital commitments). After all, the principals of the general partner must bear U.S. federal income tax on their entire share of fund gains, albeit at a much lower tax rate than tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors must bear. In other words, fund managers are increasingly concluding that the only legitimate concern of tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors is their desire to avoid filing a U.S. tax return—which arguably is satisfied by a parallel AIV—not the avoidance of an indirect U.S. tax liability.

Conclusion

In the past few years, buyout funds increasingly have begun to offer parallel AIVs to tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors to "block" UBTI and ECI from investments by the funds in pass-through operating companies. These structures are offered to investors either to satisfy the funds’ UBTI and ECI undertakings in their partnership agreements—which have specifically been drafted with parallel AIVs in mind—or simply to be "investor friendly."

Although parallel AIVs do not prevent tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors from indirectly bearing U.S. federal income tax (and actually may increase the indirect tax cost as a result of the branch profits tax), they should prevent such investors from receiving allocations of UBTI and ECI, if the fund’s partnership agreement is drafted properly.

While this enables tax-exempt investors to avoid reporting UBTI, non-U.S. investors are still technically required to file a U.S. tax return as a result of the fund’s investment in the operating LLC, even though such investors have opted out of the investment through the fund. While non-U.S. investors who have no gross ECI currently can ignore this filing requirement without penalty, they risk being taxed on their gross ECI without the benefit of related deductions if in fact they actually earned gross ECI during any year in which they failed to file a U.S. tax return.

Footnotes

1 Operating companies that are treated as flow-through vehicles for U.S. tax purposes generally are referred to herein as "operating LLCs," although such vehicles also could be formed as partnerships or as other entities if organized offshore.2 This article deals exclusively with parallel AIVs established to address UBTI/ECI concerns arising from investments in flow-through operating entities, largely because they are the most commonly used parallel AIVs. As mentioned in the introduction, however, parallel AIVs can be used to address other tax concerns (such as to avoid investing in a "controlled foreign corporation") as well as legal and regulatory concerns, which are beyond the scope of this article.

3 Code Sections 511, 512 and 513.

4 Code Section 511(a)(1).

5 Code Section 512(b).

6 Code Section 512(c)(1).

7 Treas. Reg. Section 1.6012-2(e).

8 This article assumes that all non-U.S. investors are "nonresident aliens." Under U.S. tax law, a non-U.S. citizen generally will be treated as a nonresident alien unless such person (1) is a U.S. green card holder, or (2) meets the "substantial presence test." In general, the "substantial presence test" is met (and a person is treated as a resident alien) if a person is physically present in the U.S. on 183 days or more in a calendar year.

9 Code Sections 871 and 881.

10 Code Section 897.

11 Code Sections 872 and 882.

12 Treas. Reg. Sections 1.6012-1(b)(1)(i) and 1.6012-2(g)(1)(i).

13 Code Section 884.

14 Organizing the parallel AIV as a U.S. corporation does not alleviate this higher indirect tax cost. Although a U.S. parallel AIV would not be subject to the branch profits tax, distributions to its non-U.S. shareholders would be subject to a 30% withholding tax, absent tax treaty reduction. In fact, a U.S. parallel AIV likely would produce a greater tax cost than an offshore parallel AIV because, among other reasons, all of the U.S. parallel AIV’s income would be subject to a corporate-level tax.

15 Note that if the fund has multiple parallel AIVs for separate investments, the economics of which are aggregated with the main fund, the IRS could in theory assert that each of the parallel AIVs is engaged in a "tax partnership" with the main fund and therefore that the U.S. trade or business of a parallel AIV does not terminate immediately after its disposition of the underlying operating LLC.

16 Although it is beyond the scope of this article, it may be preferable to structure the main fund’s partnership agreement as "allocation driven" as well as to comply with the other requirements of the "704(b) safe harbor" to minimize the likelihood of an IRS challenge of the special allocations of UBTI and ECI away from the opt-out partners.

17 Note that there are other ways that funds could deal with this issue. One is to purchase options to acquire equity interests in the operating LLC. Although beyond the scope of this article, there are a number of potential tax issues involved with this approach, including whether the options have been constructively exercised, that generally have made this approach unattractive to funds. Another approach is simply to allow tax-exempt and non-U.S. partners to opt out of the investment. This approach, however, often is unsatisfactory because the tax-exempt and non-U.S. partners must completely forego their economic participation in the investment, and non-U.S. investors face the same technical filing requirement discussed below.

18 For example, the IRS could assert that the parallel AIV merely holds interests in the operating LLC as an agent for its tax-exempt and non-U.S. investors, who actually are the direct, beneficial owners of the operating LLC for tax purposes. The IRS might also challenge the parallel AIV under Code Section 269, but the courts generally have construed Section 269 narrowly to situations in which the IRS has denied a "deduction, credit or other allowance," and not when the IRS has attempted to increase a taxpayer’s includible income.

19 Treas. Reg. Sections 1.6012-1(b)(1)(i) and 1.6012-2(g)(1)(i).

20 Code Sections 874(a) and 882(c)(2).

21 Treas. Reg. Sections 1.874-1(b)(1) and 1.882-4(a)(3)(i).

22 Swallows Holdings Ltd. v. Comm’r, 126 T.C. No. 6 (1/26/06).

23 See, e.g., Ardbern Co. Ltd. v. Comm’r, 120 F.2d 424 (4th Cir. 1941). In Ardbern, the Fourth Circuit held that former Section 233 (which was a predecessor to Section 882(c)(2)) did not prevent a taxpayer from deducting expenses when the taxpayer files a return claiming those deductions before the IRS determines a deficiency against the taxpayer or files a substitute return on behalf of the taxpayer.

24 Code Section 4943.

The authors would like to thank David Oliphant of Proskauer Rose LLP for his assistance.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.