* Ms. Pan is a partner in the EM practice group of Sughrue Mion, PLLC in Washington, DC. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author.

On October 31, 2007, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia preliminarily enjoined implementation of the U.S.P.T.O. New Patent Rules package announced on August 21, 2007.1 Patent holders and practitioners breathed a collective sigh of relief as the burdens and constraints of the new Rules no longer had an overwhelming immediacy. Among the Rules enjoined was a regulation mandating disclosure of related applications and patents held by a common assignee, having at least one common inventor and whose effective filing dates fell within a prescribed timing window.2 This Rule, if implemented, would have required a wholesale revision of docketing systems of many patent applicants. Despite the injunction of the Rules, the importance of having systematic disclosure of related applications to U.S.P.T.O. Examiners cannot be relegated to the backburner of patent concerns. The reasons for this are twofold. First, though the preliminary injunction of October 31, 2007 specifically voided the U.S.P.T.O.'s ability to put limits on continuation applications, number of claims and RCE requests, the restrictions against the U.S.P.T.O.'s promulgating rules relating to disclosure of related application were not as pronounced.3 Second, and perhaps more importantly, the Federal Circuit's decision of McKesson Information Solutions, Inc. v. Bridge Medical Inc.,4 imposes a duty of disclosure of proceedings in related applications that is even more far-reaching than required by the currently defunct Rules.

Procedural Background Of McKesson

Decided three months in advance of the New Rules announcement, McKesson suggests that merely disclosing related applications may not be sufficient to guard against a finding of inequitable conduct, leading to the unenforceability of a patent. In McKesson, the sole patent being litigated was U.S.P. 4,857,716 (hereafter "'716 patent" issued to Gombrich, Zook and Hendrick). The '716 patent issued from application 205,527 and shared a common parent (Serial 862,278) with the continuation-in-part application that eventually led to issuance of U.S.P. 4,835,372 (hereafter "'372 patent"). Both the '716 patent and the '372 patent were prosecuted by practitioner Schumann before Examiner Trafton and were assigned to CliniCon Inc.5 The '372 patent issued with substantially no prosecution on the merits on December 16, 1988. At that time, the '716 patent was still in active prosecution. Schumann did not disclose the allowance of the '372 patent to the common Examiner Trafton.

A third patent discussed in McKesson was U.S.P. 4,850,009, which issued to Zook and Gombrich based on application Serial 203,549, a continuation of Serial 862,149. The '549 application was filed eight days prior to the continuation application (Serial 205,527) which eventually issued as the '716 patent. Schumann did disclose the existence of the pending '549 application to Examiner Trafton, and prosecuted the '549 application. However, prosecution of the '549 application was before Examiner Lev.

Substantive Background Of McKesson

Substantively, the '716 patent relates to a patient identification system for relating items (such as medications) with patients and ensuring that an identified item corresponds to the identified patient. This is accomplished by physically attaching bar codes to the patient and their medications and providing a patient terminal bar code reader. The patient bar code reader wirelessly communicates with a base station located in a patient's room. This base station communicates with a computer system that processes and stores patient data. Thus, among the patient terminal, the base station and the system computer, the '716 teaches a "three node" communication.6 In order to prevent a patient terminal from communicating with the base station in an adjacent room, the base stations of the '716 patent include a unique identifier, communicating with the patient terminal using "the unique identifier."7

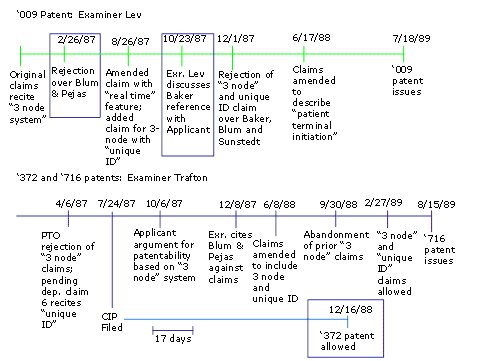

The McKesson decision focused on these two aspects of the communication system 1) the "three node" communication and 2) the "unique identifier" in discussing the prosecution history of the '716 patent.

In reply to an Office Action dated April 6, 1987, the patentee argued for patentability of claims directed to the "three node" communication feature.8 The "unique identifier" feature was recited in a separate dependent limitation as part of the parent '278 application. On December 8, 1987, the Examiner maintained the rejection of the "three node" claim over the combination of Blum and Pejas. However, the Examiner explained that the claim further including the "unique identifier" feature would be allowed if rewritten in independent form. Schumann accepted this offer on June 8, 1988, by abandoning the (parent) '278 application in favor of the '527 application, with an independent claim including the feature of claim 6 (unique identifier feature) in conjunction with the three node communication. Examiner Trafton allowed the claim on February 27, 1989, and the '716 patent issued on August 15, 1989.9

Concurrent with the prosecution of the '716 patent, Examiner Trafton allowed the '372 patent on December 16, 1988, on claims that included the three node communication but did not recite the unique identifier. As discussed above, Schumann did not disclose the (prior) allowance of the '372 patent to Trafton during prosecution of the '716 patent.

Also concurrent with the prosecution of the '716 patent, Schumann prosecuted the '549 application before Examiner Lev. Prior to a first Office Action on the merits, claims of the '549 application included recitations of the three node communication. Examiner Lev rejected these "three node communication" claims over Blum and Pejas on February 26, 1987, about ten months prior to the citation of the same reference combination in the '716 prosecution history by Examiner Trafton. Schumann did not disclose Examiner Lev's rejection over Blum and Pejas in the '549 application to Examiner Trafton in the prosecution of the '716 patent. On August 26, 1987, the patentee amended claims of the '549 application to include features of a "real time" communication and further included dependent claims to describe the three node communication in combination with the unique identifier. On October 23, 1987, 17 days after filing of the Amendment traversing the rejection of the "three node" claim in the '716 patent, Examiner Lev discussed a new reference (Baker) with attorney Schumann. The Examiner issued a formal rejection of the claims including the combination of the three node communication and the unique identifier over the combination of Sunstedt, Blum and Baker on December 1, 1987.

Up until the Office Action citing Baker, Schumann had disclosed references cited in the '549 application in the prosecution of the '716 patent. Thus, the Baker patent was not made of record in the '716 patent. On June 17, 1988, Schumann amended claims in the '549 application to include a self-initiated communication. This amendment was made to distinguish the claims over the rejection over Sunstedt, Blum and Baker, which combination included a "polling" arrangement. The '549 application issued as U.S.P. 4,850,009 on July 18, 1989.

A timeline summary of the prosecution of each of the '716, '372 and '009 patents is set forth below.

Trial Background

At trial, Schumann admitted that the disclosed address code of the co-pending '149 application was the same as the "unique identifier" in the '278 application. Thus, the trial court deemed the Baker reference, not just material but "highly material" to the '716 patent.10 Schumann attempted to characterize the Baker reference as merely cumulative to other art previously of record, referring to specifically the combination of Blum and Hawkins. However, the district court did not find this explanation of cumulative subject matter persuasive, because the same references had been before Examiner Lev in the co-pending '149 chain of applications. Nonetheless, Examiner Lev cited the additional Baker reference in rejecting claims in the co-pending case.11 The trial court inferred an intent to deceive based on collective facts, including 1) Examiner Lev locating the Baker patent on his own; 2) that Schumann became aware of the Baker patent via a telephone interview; 3) that Schumann realized that Baker could not be overcome; 4) that even though Schumann had disclosed the common prior art in the '009 and '716 patent prosecution histories, Schumann concluded that the Baker reference had no bearing on the '716 prosecution which included similar claim elements at issue in the '009 patent.

The trial court also based its conclusion of inequitable conduct on Schumann's failure to disclose the early rejection of the "three node" claims by Examiner Lev and failure to disclose Examiner Trafton's prior allowance of the '372 patent. The materiality of the two non-disclosures were discussed at length. The intent to deceive on these two items was deduced from the trial court's determination that Schumann's reasons for non-disclosure were not credible or plausible. Even giving Schumann proper good faith credit for disclosing the related applications, the court found the requisite intent to deceive to render the '716 patent unenforceable. After analyzing each item of non-disclosure individually, the trial court also considered the collective non-disclosures to support an intent to deceive.

Federal Circuit Analysis

The Federal Circuit affirmed the lower court's finding of inequitable conduct for failure to disclose 1) the early rejection in the '549 application (of the three node claims) over the combination of Blum and Pejas; 2) the Baker patent as cited in the '549 application prosecution; and 3) the allowance of the "three node" claim in the '372 patent. Therefore, even though Schumann disclosed the related applications themselves, the Federal Circuit determined that this did not outweigh evidence showing a pattern of intent to deceive by withholding their more particular prosecution events from the related cases during prosecution of the subject '716 patent.12

The Federal Circuit's McKesson decision relies heavily on the 2003 case of Dayco Products, Inc. v. Total Containment, Inc.13 Oddly, in the Dayco case, the Federal Circuit reversed a district court's summary judgment of inequitable conduct based on a fact pattern similar to the facts of McKesson.

Dayco Analysis

In Dayco, the Federal Circuit considered whether the non-disclosure of 1) a co-pending application; 2) a reference cited in the co-pending application; and 3) rejection of similar subject matter in the co-pending application were sufficient to support a conclusion of unenforceability due to inequitable conduct. The Dayco decision stated the basic two part inequitable conduct inquiry as follows.

In order to prove inequitable conduct in the prosecution of a patent, the defendant must have provided evidence of ... failure to disclose material information... coupled with intent to deceive. Both intent and materiality are questions of fact that must be proven by clear and convincing evidence. The inequitable analysis is performed in two steps comprising, first, a determination of whether the withheld reference meets a threshold level of materiality and intent to mislead, and second, a weighing of the materiality and intent in light of all the circumstances to determine whether the applicant's conduct is so culpable that the patent should be held unenforceable.14

The Dayco decision found all three types of non-disclosed information were material, but reversed summary judgment for lack of findings regarding requisite intent. Significant aspects of the Dayco decision are discussed below.

The patentee attempted to discount the non-disclosure of the co-pending '196 application due to the (eventual) filing of a terminal disclaimer over another patent (the '143 patent) that would result in a patent term severely shorter than any term that would result from a terminal disclaimer over the '196 application. The Federal Circuit did not specifically comment on the propriety of the patentee's theory that information that is material at the outset of a prosecution may become immaterial (through the filing of the terminal disclaimer that severely shortened that patent term). Rather, even accepting such a theory, the Federal Circuit explained that a co-pending application can lead to a double patenting rejection even if a terminal disclaimer in the patents would not lead to a reduction of claim term. This is because the shortening of patent term is not the only result of overcoming a double patenting rejection by terminal disclaimer. A provision of common ownership also further limits the rights of a patent subject to a double patenting rejection. Therefore, a co-pending application can meet the threshold level of materiality.

In the Dayco case, the Federal Circuit determined that requisite intent to deceive could not be inferred because the patentee did, in fact, draw the U.S.P.T.O.'s attention to the existence of co-pending applications. Such disclosure points away from an intent to deceive. On this matter, the Dayco court determined that on this disclosure, and absent other factual finding to support an intent to deceive, that there was no basis to support a finding of unenforceability.15 It is emphasized here that the same attorneys prosecuted both the subject patents-in-suit and also the '196 application. The subject patents were examined by Examiner Arola, and the '196 application was being examined by Examiner Nicholson. The subject patents were identified to Examiner Nicholson, but the reverse disclosure was not made to Examiner Arola. Thus, there was a unilateral disclosure of applications and not a mutual one. However, the Federal Circuit determined that the one-way disclosure points away from an intent to deceive.16 The finding of no intent to deceive was consistent with prior Federal Circuit precedent regarding unilateral disclosure of co-pending applications.17

The Dayco case also involved failure to disclose the Wilson reference used by the Examiner in the first ('196) application in the second application that resulted in the patent-in-suit. The Federal Circuit noted that the citation of the Wilson reference by Examiner Nicholson (the '196 Examiner) was informative but not dispositive. Here, the patentee had explained the non-disclosure of the Wilson patent because it was not the same field of invention and thus further afield from the cited art. The defendant countered that statement with its own evidence to show that the withheld reference was not cumulative to any information before the Examiner. Applying the decision in FMC v. Manitowoc,18 which takes into account the claims of the patent-in-suit and the remaining prior art references, the Federal Circuit determined that there were plausible reasons for non-disclosure of Wilson that do not support an intent to deceive. On this ground, the Federal Circuit reversed summary judgment regarding the intent component for the non-disclosed patent.19

In Dayco, the Federal Circuit also determined that an unpatentability decision of another Examiner reviewing a substantially similar claim meets a "reasonable examiner" threshold of materiality.20 Here, the Federal Circuit had to consider the combination of the non-disclosed '196 application and the non-disclosed Wilson reference, where Examiner Nicholson had rejected claims with identical subject matter in view of Wilson. The Federal Circuit stated that the existence of rejections of substantially similar claims meets requirements for materiality.21 However, there must be a separate factual inquiry regarding intent.22

Despite strong parallels between McKesson and Dayco, the Federal Circuit came to opposite conclusions. Both the Dayco and McKesson decisions refer to MPEP 2001.06(b), which pertains to the duty of disclosure of information relating to co-pending U.S. patent applications. In the time intervening between the two decisions, MPEP 2001.06(b) remained substantially unchanged, except for a modification of the current edition which makes specific reference to the Dayco decision. MPEP 2001.06(b) provides:

The individuals covered by 37 C.F.R. §1.56 have a duty to bring to the attention of the examiner, or other Office official involved with the examination of a particular application, information within their knowledge as to other copending United States applications which are "material to patentability" of the application in question.

. . . .

Accordingly, the individual covered by 37 C.F.R. § 1.56 cannot assume that the examiner of a particular application is necessarily aware of other applications which are "material to patentability" of the application in question, but must instead bring such other applications to the attention of the Examiner > See Dayco Prod., Inc. v Total Containment, Inc., 329 F3d 1358, 1365-66, 66 USPQ2d 1801, 1806-08 (Fed. Cir. 2003) < For example, if a particular inventor has different applications pending in which similar subject matter but patentably indistinct claims are present that fact must be disclosed to the examiner of each of the involved applications. Similarly, the prior art references from one application must be made of record in another subsequent application if such prior art references are "material to patentability" of the subsequent application. []

. . . .

If the application under examination is identified as a continuation, divisional, or continuation-in-part of an earlier application, the examiner will consider the prior art cited in the earlier application. The Examiner must indicate in the first Office action whether the prior art in a related earlier application has been reviewed. Accordingly, no separate citation of the same prior art need be made in the later application.23

Because the basic MPEP principles were the same at the time of Dayco and at the time of McKesson, it is puzzling why two similar fact patterns produced such different results on the issue of inequitable conduct. Though issues of inequitable conduct are fact-driven, it is significant that the Dayco opinion treats each individual non-disclosure individually.24 In contrast, the McKesson treats the non-disclosure in the aggregate, thereby forming a "pattern" out of the non-disclosures collectively to buttress a finding of an intent to deceive the Examiner.25 This is true even though two out of three non-disclosures of McKesson seem questionable as references "material" to patentability.26

For example, Schumann's failure to make an early disclosure of the rejections over Blum and Pejas in the rejections of the co-pending '149 application served as a basis for a finding of inequitable conduct. However, the combination of Blum and Pejas was eventually also made in the rejection of claims in the '716 patent. Therefore, it cannot be said such disclosure was withheld, since such information actually was considered in the prosecution of the patent-in-suit.27 Nonetheless, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court's determination of inequitable conduct on the basis of this non-disclosure.

Similarly, the failure to disclose the allowance of the '372 patent also served as a basis in the finding of inequitable conduct, even though the existence of the application issuing as the '372 patent was disclosed to Examiner Trafton. In fact, Examiner Trafton actually examined and allowed the '372 patent.28 The Federal Circuit acknowledged that the disclosure of the allowance of the '372 patent could have been cumulative, if the patentee had affirmatively shown that Examiner Trafton remembered issuing the '372 patent. However, the record did not bear out whether such consideration was actually made during the course of prosecuting the '716 patent. The Federal Circuit relied on MPEP 2001.6(b), stating that a prosecuting attorney should not assume that an Examiner retains details of every pending file in his mind when he is reviewing a particular application.29

In further regard to the failure to disclose the allowance of the '372 patent, Federal Circuit precedent would allow prospective correction of the double-patenting invalidity raised by the '372 patent by filing of a terminal disclaimer after issuance of the '716 patent.30 In such a circumstance, the patentee garners no benefit of non-disclosure since there is both restriction on assignment and also reduced patent term with the post-issuance filing of the terminal disclaimer. These facts would seem to undermine the materiality of the lack of disclosure of the '372 patent allowance.

The Federal Circuit spent considerable time explaining how patentee's failure to cite Baker supported the inequitable conduct finding. Accepting that Baker was highly material, the Federal Circuit reviewed a larger body of precedent regarding "intent."

The intent element of inequitable conduct is in the main proven by inferences drawn from facts, with the collection of inferences permitting a confident judgment that deceit has occurred. However, inequitable conduct requires not intent to withhold, but rather intent to deceive. Intent to deceive cannot be inferred simply from the decision to withhold information where the reasons given for the withholding are plausible. In addition, a finding that particular conduct amounts to "gross negligence" does not of itself justify an inference of intent to deceive; the involved conduct, viewed in light of all the evidence, including evidence indicative of good faith, must indicate sufficient culpability to require a finding of intent to deceive. The party asserting inequitable conduct must prove a threshold of materiality and intent by clear and convincing evidence. The court must then determine whether the questioned conduct amounts to inequitable conduct by balancing the levels of materiality and intent, with a greater showing of one factor allowing a lesser showing of the other.31

Based on Federal Circuit precedent, the decision in McKesson could very well have been decided solely on the patentee's non-disclosure of the highly pertinent Baker reference, having disclosure which contradicted representations made by Applicant in attempting to obtain issuance of the '716 patent. However, rather than considering such non-disclosure individually, the Federal Circuit determined a pattern of intent to deceive, based on the status of claims and rejections in co-pending commonly assigned patents, even though the applications themselves were actually disclosed during prosecution of the subject patent. Rather than excusing the patentee's conduct based on the application disclosure, which would be supportable in view of the Federal Circuit's decisions in Dayco and Akron Polymer, the Federal Circuit took the opposite stance. The court relied heavily on the U.S.P.T.O.'s procedural documentation requirements, leading to more rigorous disclosure requirements of not only co-pending application disclosures, but also particular aspects of their prosecution.

Considerations Going Forward

In view of McKesson, assignees can guard against unenforceability decisions due to lack of disclosure by implementing a systematic method of tracking related patent applications which claim similar subject matter, and disclosing those applications in all such related applications. Such systems should further track rejections made in the applications so that information disclosure statements can be cross-filed in the cases. The system should also be able to track the status of the related applications to apprise the Examiners of all cases of the status of related subject matter.32 Disclosure of related applications should minimally comprise those cases which share a continuation, continuation-in-part relationship or divisional relationship. Disclosure of related applications should also include additional cases where an assignee's application serves as the basis for a provisional double-patenting rejection for another one of its applications. Those entities that were poised to meet requirements of prior proposed Rule 1.78(f) should be readily able to conform with the additional obligations that are imposed by McKesson. The Federal Circuit warns that firms cannot insulate attorneys from charges of inequitable conduct by instituting policies that prevent attorneys from complying with their disclosure requirements.

In the near term, Applicants may simply decide to err on the side of over-disclosure. However, a tendency towards being over-inclusive also has its drawbacks. For instance, over-inclusive disclosure would run counter to MPEP 2004(13) which states:

It is desirable to avoid submission of long lists of documents if it can be avoided. Eliminate clearly irrelevant and marginally pertinent cumulative information. If a long list is submitted, highlight those documents which have been specifically brought to applicant's attention and/or are known to be of most significance. See Penn Yan Boats, Inc. v. Sea Lark Boats, Inc., 359 F. Supp. 948, 175 USPQ 260 (S.D. Fla. 1972), aff'd, 479 F.2d 1338, 178 USPQ 577 (5th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 414 U.S. 874 (1974). But cf. Molins PLC v. Textron Inc., 48 F.3d 1172, 33 USPQ2d 1823 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

If an Applicant errs too far on the side of over-disclosure, and by happenstance offers an explanation of the submitted information that does not identify the most relevant disclosure or applications, then this may also serve as a basis of inequitable conduct. In particular, a court may deem that the Applicant was attempting to "bury" the most pertinent information in a "blizzard of paper."33

It is also noted that the McKesson decision suggests documenting why a reference was not cited, including the reason for non-disclosure of a particular reference.34 However, it is not clear whether subjective explanations, such as a purported "good faith" reason for non-disclosure will be sufficient to protect against a finding of inequitable conduct because the standard of materiality is an objective one, not a subjective one. In the past year, the Federal Circuit has not accepted such subjective explanations for non-disclosure when considering whether inequitable conduct has occurred.35 Therefore, merely documenting the reason why a reference was not disclosed may not be a worthwhile exercise.

In the long term, it is possible that the arc of case law relating to inferences of intent to deceive will swing back towards that expressed by Judge Newman, who offered the following in a dissenting opinion in McKesson:

It is not clear and convincing evidence of deceptive intent that the applicant did not inform the examiner of the examiner's grant of a related case of common parentage a few months earlier, a case that was examined by the same examiner and whose existence has explicitly been pointed out by the same applicant. Nor is it clear and convincing evidence or deceptive intent that the applicant did not cite a reference that the applicant in the same related case, and that had been explicitly discussed with the same examiner in the related case. Whether or not the examination was perfect, invalidation based on the charge of withholding material information for purposes of deception requires more than was shown [in the McKesson case].

What is important presently is an ability to demonstrate a systematic method to report the status of related applications. With such a system in place, material subject matter can be easily tracked and disclosed to relevant Examiners. The use of such a system will rebut any notion that an organization has turned "a blind eye" towards its disclosure obligations, and the consistency afforded by such a system will help avoid gaps in disclosures which could give rise to an intent to deceive. Finally, the disclosure of the most pertinent art for consideration by the U.S.P.T.O. only helps to maintain the viability of the patent should it ever undergo an invalidity challenge based on prior art.

Footnotes

1. SmithKline Beecham Corp. v. Dudas; 1:07CV846 (E.D.Va., October 31, 2007), enjoining implementation of "Changes to Practice for Continued Examination Filings; Patent Applications Containing Patentably Indistinct Claims, and Examination of Claims in Patent Applications; Final Rule," Fed. Reg. 46716 (August 21, 2007).

2. Rule 1.78(f) Applications and patents naming at least one inventor in common. (1)(i) The applicant in a nonprovisional application that has not been allowed (§ 1.311) must identify by application number (i.e., series code and serial number) and patent number (if applicable) each other pending or patented nonprovisional application, in a separate paper, for which the following conditions are met:

- The nonprovisional application has a filing date that is the same as or within two months of the filing date of the other pending or patented nonprovisional application, taking into account any filing date for which a benefit is sought under title 35, United States Code;

- The nonprovisional application names at least one inventor in common with the other pending or patented nonprovisional application; and

- The nonprovisional application is owned by the same person, or subject to an obligation of assignment to the same person, as the other pending or patented nonprovisional application.

3. See SmithKline Beecham, Order 1:07CV846 (October 31, 2007), at paragraphs 4 and 5.

4. 82 USPQ2d 1865 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

5. CliniCon was one of several assignees of the patent-in-suit prior to its assignment to McKesson.

6. 82 USPQ2d at 1867.

7. Id.

8. Amendment dated October 6, 1987.

9. 82 USPQ2d at 1868.

10. Id. at 1872.

11. Id.

12. Id. at 1875.

13. 66 USPQ2d 1801 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

14. Id. at 1804 (internal citations omitted). The Dayco decision did further expound on the definition of "materiality" as information not cumulative to information already of record or being made of record in the application, and where the information establishes, by itself or in combination with other information, a prima facie case of unpatentability of a claim; or the reference refutes, or is inconsistent with, a position the applicant takes in opposing an argument of unpatentability relied upon by the Office or asserting an argument for patentability. Id. at 1805, n2.

15. Id. at 1811.

16. Id. at 1807.

17. Akron Polymer Container Corp. v. Exxel Container Inc., 47 USPQ2d 1533, 1534 (Fed. Cir. 1998). In that case, the disclosure of the co-pending application in the patent-in-suit did eventually occur after allowance of the patent-in-suit. Id. at 1534.

18. 5 USPQ2d 1112, 1115 (Fed. Cir. 1987).

19. 66 USPQ2d at 1807-08.

20. Id.

21. Id. at 1808.

22. Id

23. Such separate citation should be made if Applicant wishes to have the list of references indicated on the issued patent. MPEP 609.02(A)(2). The version of MPEP 2001.6(b) during the timeframe of prosecution of the Dayco patents differed only slightly. In the last paragraph, the language "If" replaced "Normally if" and the reference to divisional applications was added to the current version of MPEP 2001.06(b).

24. Dayco, 66 USPQ2d at 1811 (directing lower court on remand how individual non-disclosures should fare absent additional circumstances to support each allegation of inequitable conduct).

25. Even post-McKesson, it appears the courts approach the inequitable conduct matter on an individual item of non-disclosure, rather than collectively aggregating each non-disclosure event to show intent. See Eisai v. Teva, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 94827 at *17-18 (D.N.J.)(discussing individual detailed pleading requirements for inequitable conduct issues).

26. See dissenting opinion, 82 USPQ2d at 1886.

27. Molins PLC v. Textron, Inc., 33 USPQ2d 1823, 1832 (Fed. Cir. 1995).

28. The allowance of the '372 patent could have served as a basis of an obviousness-type double patenting rejection, which would have implicated a reduced patent term for the '716 patent and which would have provided a restriction on assignment of the '716 patent.

29. 82 USPQ2d at 1886. See also MPEP 2004(9). Do not rely on the examiner of a particular application to be aware of other applications belonging to the same applicant or assignee. It is desirable to call such applications to the attention of the examiner even if there is only a question that they might be "material to patentability" of the application the examiner is considering. >See Dayco Prod., Inc. v. Total Containment, Inc., 329 F.3d 1358, 1365-69, 66 USPQ2d 1801, 1806-08 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (contrary decision of another examiner reviewing substantially similar claims is 'material'; copending application may be 'material' even though it cannot result in a shorter patent term, when it could affect the rights of the patentee to assign the issued patents).< It is desirable to be particularly careful that prior art or other information in one application is cited to the examiner in other applications to which it would be material. Do not assume that an examiner will necessarily remember, when examining a particular application, other applications which the examiner is examining, or has examined. **>A "lapse on the part of the examiner does not excuse the applicant."< KangaROOS U.S.A., Inc. v. Caldor, Inc., 778 F.2d 1571, 1576, 228 USPQ 32, 35 (Fed. Cir. 1985)**>; see also MPEP § 2001.06(b).<

While the MPEP does not have the force of law, it is entitled to judicial notice as an official interpretation of statues or regulations as long as it is not in conflict therewith. Litton Sys., Inc. v. Whirlpool Corp., 221 USP 97, 107 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

30. In re Metoprolol Succinate Litigation, 83 USPQ2d 1545, 1551 (Fed. Cir. 2007) n.4.

31. 82 USPQ2d at 1876.

32. Id. at 1875.

33. eSpeed Inc. v. BrokerTec USA, 82 USPQ2d 1183, 1189 (Fed. Cir. 2007); Baxter Int'l Inc. v. McGaw, Inc., 47 USPQ2d 1225, 1231 (Fed. Cir. 1998).

34. 82 USPQ2d at 1880, citing MPEP 2004(18).

35. Monsanto Co. v. Bayer Bioscience N.V., 85 USPQ2d 1582, 1592 (Fed. Cir. 2008) citing Cargill, Inc. v. Canbra Foods, Ltd., 81 USPQ2d 1705, 1710-11 (Fed. Cir. 2007) but compare Dayco, 66 USPQ2d at 1808.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.