The Rules And Risks Are Rapidly evolving for financing new power plants and acquisitions.

- In March, 2007, the Sierra Club and Kansas City Power & Light (KCP&L) finalized a settlement allowing for the construction of an 850 MW coal plant. In exchange, KCP&L will add 400 MW of wind energy and reduce CO2 emissions 20% by 2020.

- The first application to build a new U.S. nuclear power plant in 30 years has been filed with the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission ("NRC"). The NRC expects to receive about 18 more applications by the end of 2008.

- In 2006, installed wind capacity rose by 27% from the previous year, reflecting investments of $3.7 billion.

- The largest private leveraged buyout in U.S. history was recently approved by shareholders and federal regulators. TXU had been the target of intense opposition from national environmental groups for their plans to build 11 new coal-fired power plants. Upon announcing their offer for TXU, the private bidder dropped plans for 8 of the 11 plants, preventing 56 million tons of CO2 emissions annually and earning endorsements for the deal from the Environmental Defense Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Counsel.

What do all these events have in common? They all point to the fact that, despite the absence of federal greenhouse gas (GHG) regulation, developers of power generation projects have already changed their strategy from recent years, and are encountering an intensity of opposition and potential incentives in ways unforeseen just a few years ago.

In particular, the uncertainty over the timing and shape of future climate-related regulation will dramatically impact the financing of coal, nuclear, gas, and renewable energy projects, in both positive and negative directions. For example, if a carbon cap and trade system were established nationally, parties to numerous power sale, purchase and trading agreements (existing and prospective) would need to determine where the burden of a new cost should fall. In theory, Congress would probably intend that the burden should be allocated broadly across the economy; however, traditional PPAs, trading agreements and capacity markets are not constituted to pass the risk along in a uniform manner. Moreover, public utility commissions are generally resistant to allowing power rates to increase, whereas another constituencyenvironmental regulatorstends to see power price increases as a necessary price to pay to begin combating global warming.The precise impacts on future revenues and costs are uncertain and are likely to remain fluid for the next few years. In the face of this uncertainty, however, financing decisions are being made on a daily basis.

Project Risks And Opportunities

Any power project developed in the United States is currently affected by (i) a market resulting from a state or regional greenhouse gas (GHG) emission target, or (ii) a national voluntary market for GHG reductions, and (iii) the specter of looming federal regulation, the details of which are unknown. These markets and regulations will offer alternative methods of compliance if GHG reductions are imposed on a carbon-intensive power project such as a coal plant or aging gas plant. A brief description of the mandatory and voluntary carbon markets absent the 600 pound federal gorillaare described below.

Mandatory Carbon Regulation

States

California

In September 2006, California enacted AB 32, which caps the state's GHG emissions at 1990 levels by 2020. California is the first state to enact economy-wide mandatory GHG emission reductions, which become effective in 2012. Its impact is already undeniable; in September 2007, California and ConocoPhillips announced an agreement in which ConocoPhillips will off-set the GHGs from a refinery expansion project until the AB 32 caps take effect. Additionally, SB 1368 imposes a greenhouse gases emissions performance standard for baseload generation, no greater than combined cycle natural gas emissions levels. This standard applies to both long-term energy contracts and new ownership investment entered into by load-serving entities, including municipal power agencies..

Regional Markets

Two key regional organizations have been created in the U.S. to set up mandatory state and regional carbon reduction requirements.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) includes 10 northeast and mid-Atlantic states that have agreed to implement legally binding GHG emissions caps. Participating states will begin capping GHG emissions in 2009, and a trading program will also be created.

The Western Climate Initiative ("WCI"), which includes 5 western states, has established a GHG reduction target of 15% below 2005 levels by 2020. By August 2008, market-based mechanisms will be developed to help achieve the goals.

Federal Regulation Coming: When and How?

The question is not whether there will be federal regulation of GHGs, but what the shape of the regulations will be and when they will become effective. Calls for action on climate change and the emission of greenhouse gases are coming from public interest groups, government bodies, shareholders and, increasingly, industry groups around the country. Currently, eleven climate bills are pending before the U.S. Congress.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts v. EPA, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the EPA has authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate tailpipe emissions of greenhouse gases and that the EPA's current rationale for not regulating CO2 emissions was inadequate, forcing (sooner or later) a re-evaluation of the decision by the EPA not to regulate CO2 emissions. In a related case, a federal court recently affirmed Vermont's power to regulate GHG emissions from automobiles. Although this decision involved regulation of tailpipe emissions, it will have significant ramifications for energy facilities and other stationary sources. The section of the Clean Air Act governing new source performance standards and the establishment of national ambient air quality standards contains language identical to that construed by the Court in Massachusetts v. EPA. In fact, the EPA is already considering the possibility of including greenhouse gases among the pollutants considered in new source review.

Finally, the recent U.S. House version of the energy bill contained a national renewable portfolio standard ("RPS") of 15% by 2020, suggesting additional uncertainties.

Financing Example from a Voluntary Market

We recently worked on a project in Texas, a voluntary market, to convert feedlot methane into pipeline-grade natural gas. The financial forecast of a future stream of gas and carbon revenues used to secure financing was undertaken without securing a firm sales agreement for the carbon credits. This project employed an innovative cross-collateralization framework which may permit future carbon credits to secure future tax-exempt financing. The developer has recently signed a gas sales agreement in principle with Pacific Gas & Electric Company, relating to a similar project in California, which as of 2012, will no longer be a voluntary market. Projects capturing methane present significant opportunities to benefit from a carbon regulatory regime because methane has roughly 20 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. Even where the methane is burned for energy and the carbon dioxide emissions are subtracted, a methane capture facility will generate credits equal to roughly 17 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of methane captured and burned. Furthermore, while carbon credits are currently selling for about $4 per ton in the U.S. voluntary market, futures in the mandatory European exchange recently sold for nearly $30 per ton.

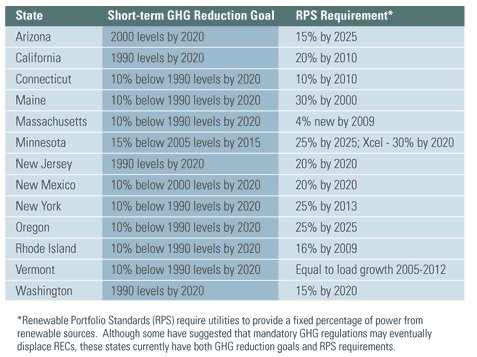

Figure 1. U.S. states with both GHG and Renewable Portfolio Standard requirements.

Source: Pew Center on Global Climate Change

Unique Challenges and Opportunities Depend on Project Type

1. Coal Generation Units-Air Permits and Carbon Mitigation

Even where there is no current regulation of carbon dioxide emissions, the reality facing air permit applicants of coal-fired electric generation units today is that the applicant must have a carbon mitigation plan if they expect to obtain approval.

National environmental groups are participating in a well-coordinated campaign to oppose the use of coal as a primary source of energy. The KCP&L settlement and other similar agreements have set a high standard for coal developers to meet in mitigating the GHG impacts of coal-fired plants to successfully obtain air permits. Federal regulators are lagging behind until rulemaking catches up with the Massachusetts v. EPA decision. As the EPA recently said: "the Agency is working diligently to develop an overall strategy for addressing the emissions of CO2 and other GHGs under the Clean Air Act. However, the EPA does not currently have the authority to address the challenge of global climate change by imposing limitations on emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases in PSD permits."

Because coal plants with gasification technologies, such as IGCC, offer the eventual potential for more cost-effective carbon capture and storage, environmental advocates and regulators in some states will expect new projects to be "retrofitable" for carbon-capture so that new technologies can be applied later. Clearly, lenders and investors are now unwilling to finance carbon capture projects on an unsubsidized basis.

2. Nuclear Power Projects

Many states are considering nuclear power as one of many options to reduce carbon dioxide emissions in their climate planning process. Since nuclear power generation results in virtually no GHG emissions, nuclear power projects will not be subject to GHG restrictions. The value to the project will depend on whether the facility is located in a state that is a signatory to a GHG reduction plan, or whether federal GHG regulation occurs.

3. Gas Projects

New Gas Development

Because modern natural gas combined cycle plants emit less than half of the carbon content of a modern coal plant, the costs of complying with any required GHG reductions will be substantially lower for natural gas plants sited in states within RGGI or WCI markets. The exceptional challenges to air permits discussed in reference to coal plants have not impacted gas plant applications so far, though including a carbon mitigation plan as part of an air permit application is still a wise course of action. As is the case with coal plants, if the plant is located in a state outside the RGGI or WCI regions, project planners should include future costs of complying with GHG regulations in the case of future state or federal regulation.

Gas Project M&A Activity

Similar issues arise for the financing of acquisitions of existing gas projects, except that existing plants would have a current air permit, and older plants, such as gas steam plants, are likely to have substantially higher carbon content in their emissions than newer combined-cycle plants. In the eastern U.S., tightening restrictions on the emissions of SO2, mercury and NOX will also be a significant factor in older plants, which will likely have higher compliance costs than newer plants. The most challenging issue for managers of gas-fired portfolios, however, will be how to manage the risks imposed by various regulatory alternatives such as a carbon tax versus a cap-and-trade regime.

4. Renewables

Renewable energy projects may qualify in some circumstances for renewable energy credits (RECs). Whether the project qualifies for RECs depends on specific state requirements, such as whether trading is allowed across state lines.

A REC is equal to the environmental attributes of 1 MWh of power generated from renewable sources and generally sold into the market where it originated. RECs may be used to fulfill renewable portfolio standard requirements that require utilities to sell a certain percentage of their energy as renewable energy. In certain states, the value of the REC may be greater than the value of the electricity generated by the project.

The importance of RECs to financing wind projects can be demonstrated by noting that while the average regional market price of wind power ranges from about $30-$50/MWh, the value of a REC in the voluntary market has ranged from about $1-$10/MWh, with the recent compliance cost in states with RPS requirements as high as $50/MWh or more. Some long-term estimates of $15/MWh have been made in those RPS states. In other words, revenues from the sale of RECs may account for less than 10% to over 50% of the total revenues of a wind generation project in the U.S., apart from the substantial tax benefits available to renewable energy projects, which are beyond the scope of this article.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.