Preamble

The article The equity bridge deals with which tax items and other accounting items should be taken into account when calculating from enterprise value to equity value when selling a business.

The article explains what is meant by correcting for deviations from normalized working capital (NWC), including the significance of choosing closing accounts as opposed to a locked box balance as the basis for the calculation of working capital. Then it is discussed how to correct for net debt (net debt) and surplus liquidity (cash / cash equivalents).

Finally, the article considers how to calculate enterprise value using the EBITDA x multiple, below how to calculate the multiple mathematically using a modified Gordon's valuation model.

Keywords: The equity bridge, enterprise value, equity value, normalized working capital, closing accounts, locked box, Gordon's valuation model.

1. INTRODUCTION

When you are selling a business, you will find that the advisers on both the buyer's and the seller's side use words and expressions that at the start of the transaction may seem foreign and unfamiliar to the person who is selling their business. The article The equity bridge deals with which tax items and other accounting items should be taken into account when calculating from enterprise value to equity value when selling a business. However, as the sales process progresses, the seller will experience that what were initially foreign and unfamiliar words and expressions turn out to be precise formulations of critical elements when determining the purchase price. Examples of such expressions are the equity bridge, and from enterprise value to equity value, which describes which tax items and other accounting items must be taken into account when calculating the final value of the company (purchase price).

In this article, we will address three critical components that directly affect how much money the seller will receive for their shares. The three components are closely linked, but are nevertheless three different factors that influence the purchase price, and they are:

- Deviation from normalized working capital (normalized working

capital / NWC);

- Net debt (net debt); and

- Cash / cash equivalents / surplus liquidity (cash / cash equivalents)

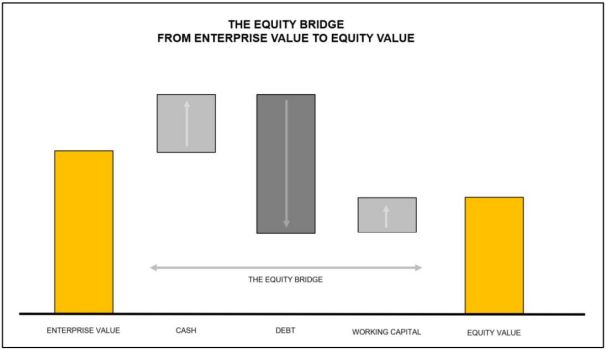

The three components together make up the equity bridge, and can be shown as follows.

We will start by getting an overview of where we are in the process of selling the company.

2. ENTERPRISE VALUE

2.1 Enterprise value as a starting point for the share value

Enterprise value (EV) is the fair value of all assets in the business, i.e. the fair value of all assets in the entire group.

There are many reasons why almost all M&A transactions are based on enterprise value. Firstly, enterprise value will show the value of the entire business, not just the equity. Secondly, enterprise value ignores how the business is financed, i.e. it ignores the capital structure in the balance sheet. Thirdly, the use of enterprise value will make it easier to compare your sales with the sales of other similar businesses, as when calculating enterprise value , one ignores individual circumstances to a certain extent linked to the businesses, such as tax matters, pensions and dividends.

Enterprise value can be calculated on the basis of a number of different valuation models depending on the business the company operates, the phase the company is in and the industry it is in. The valuation models are often divided into profit and cash flow-oriented models (normal profit, EBITDA x multiple, net discounted cash flow, etc.), and balance sheet-oriented models (accounting value, net asset value method, etc.).

One of the simplest models used to calculate enterprise value is to multiply group EBITDA by a multiple, where the multiple is either calculated from multiples from comparable actually completed transactions (pure-play companies), or calculated based on a modified Gordon's valuation model.

2.2 Enterprise value, operating capital and normalized working capital

Enterprise value consists of operating capital and working capital. Working capital is the fair value of all the assets in the business that are used to produce goods and services, such as machinery and other operating assets. Working capital is net assets that are critical to the liquidity of the business, such as accounts receivable, goods, accounts payable, operating credit and overdraft.

In practice, determining the fair value of the company's working capital will not present particular difficulties. linked to the businesses, such as tax matters, pensions and dividends. But when it comes to working capital, or more precisely, normalized working capital, and the relationship to net debt, and excess liquidity (cash / cash equivalents), the picture becomes more complex.

3. NORMALIZED WORKING CAPITAL

Normalized working capital and deviations from normalized working capital are important concepts in all M&A transactions, which we will look at in more detail in point 3.1. The concept of working capital has a fixed core, but the demarcation between net debt and cash and cash equivalents can be more complex to assess, which we will look at in more detail in point 3.2. We will look at how it should be adjusted for normalized working capital in point 3.3.

The importance of calculating the working capital on a locked box balance sheet or closing accounts must be looked at in more detail in point 3.4. In point 3.5 we will look at the actual normalization of the working capital.

3.1 Normalized working capital, what exactly is it?

When a business is to be sold, it is sold under the assumption of continued operation (going concern). In order for the business to be able to operate as normal throughout the transaction process, the business must have sufficient liquidity to be able to operate from day to day, so-called working capital.

This means that the company must have enough liquidity to pay salaries and trade payables as they fall due. Liquidity to pay when due is obtained from payments from customers who pay accounts receivable when due, and liquidity from the company's bank account, operating credit or overdraft.

But the business should not have too much liquidity, nor should it have too little liquidity, but it should have just the right amount of liquidity, i.e. normal working capital.

In a number of textbooks, the key financial figures related to liquidity are set out, such as:

- Liquidity ratio 1 = current assets / short-term debt, should be

greater than 2

- Liquidity ratio 2 = (current assets - inventory) / short-term

liabilities, should be greater than 1

- Liquidity level 3 = bank deposits / short-term debt, should be

greater than 33%

- Liquidity ratio 4 = bank deposits / short-term debt, measures the cash ratio

Based on financial key figures, the determination of what is normal working capital in a company will be subject to negotiations between the seller and the counterparty, the buyer.

When the buyer and seller agree on what is normalized working capital, this normalized working capital must be compared with the company's actual working capital. This difference between normalized working capital and actual working capital must be corrected for in the purchase price. This difference is often called deviation from normalized working capital. This means that if the business has surplus liquidity, i.e. liquidity that is too high in relation to the business being run, the seller will be paid extra for this difference.

If the business has too tight liquidity in relation to the normalized working capital, the purchase price will be reduced accordingly.

As an example, it is conceivable that if the seller agrees with the buyer that a cash element is covered by the normalized working capital, the seller will not be paid anything extra for this cash element. But if the seller, during the negotiations, concludes that the cash element is not part of normalized working capital, the seller will be paid extra krone-for-krone for this cash element.

This shows how critical the determination of the normalized working capital is for the determination of the final purchase price.

3.2 Which items should be included in the working capital?

The next question is therefore, which items should be taken into account when determining the working capital?

The clear starting point is that cash, accounts receivable, goods, trade payables and operating credit are part of working capital. At the same time, operating assets and interest-bearing debt are not part of the working capital.

When it comes to the closer demarcation between normalized working capital and working capital / net debt, there may be more doubt as to whether an accounting item should be considered part of the working capital or as net debt. This can have great significance for the seller of a business because a debt item that is considered part of the normalized working capital is not corrected for when calculating the purchase price, but if, on the other hand, the debt item is considered part of the net debt, a correction will be made for this in the purchase price crown-for-crown.

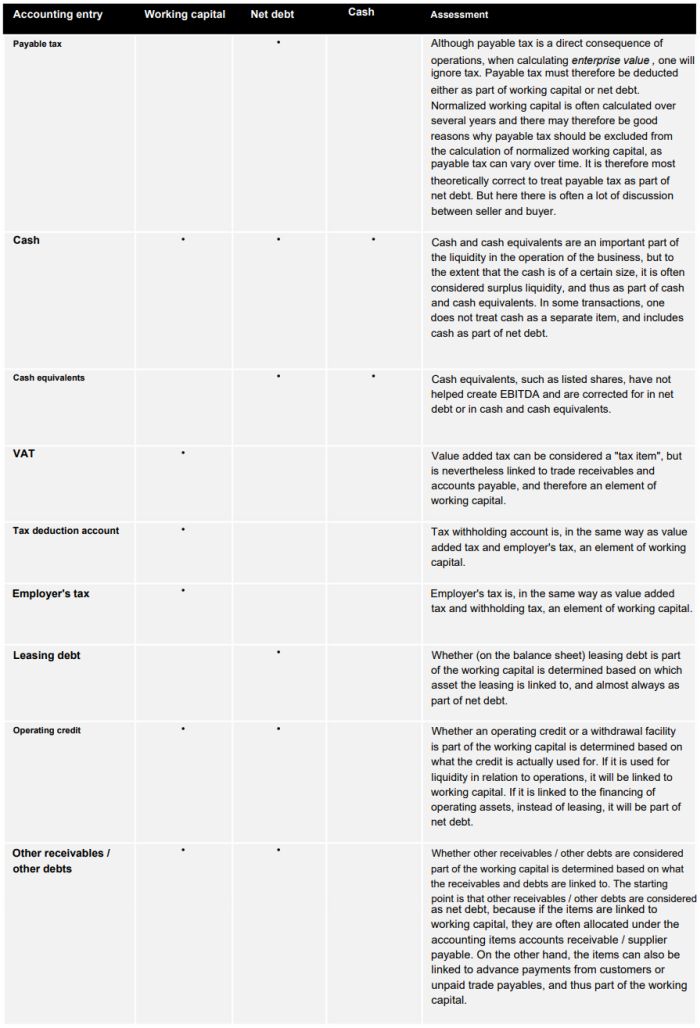

Accounting items where doubts often arise are, for example, the accounting items payable tax, cash / cash equivalents, value added tax due, tax deductions, employer's tax due, outstanding leasing debt and other receivables / other debt, as shown in the table below.

3.3 How should one adjust for normalized working capital

The next question is how should it be adjusted for normalized working capital? Should it be adjusted for total net working capital, or only for the surplus or deficit?

The assets included in the calculation of net working capital are already part of the enterprise value. One must therefore not adjust for total net working capital.

A prerequisite for calculating enterprise value is that the business has sufficient liquidity from a going concern perspective. This means that the enterprise value must only be adjusted for the actual deviation from normalized working capital, i.e. the difference between normalized working capital and the actual working capital in the business, i.e. the surplus or deficit.

The problem is that the normalized working capital we use varies according to whether the business is in the start-up phase, is a growth company, operates in a sector subject to economic fluctuations, or is a stable, well-run and solid business.

3.4 Working capital in relation to locked box and closing accounts

The next question is whether normalized working capital is affected by whether one chooses a locked box balance sheet or closing accounts as the basis for calculating the purchase price.

Locked box means that the buyer and seller agree to use a specific balance sheet date as the basis for calculating the purchase price, for example the balance sheet date for the most recently submitted annual accounts (locked box). The idea is that the annual profit from and including the locked box date accrues to the buyer, while the seller is compensated in the form of a specific interest amount that is calculated by multiplying the calculated fair value of the equity in the locked box How should one adjust for normalized working capital the date with a more specifically agreed interest rate. This interest rate is determined based on a negotiation between the parties, and can vary from 0% to 11%, and is thus an important part of the negotiations relating to the final purchase price.

When using closing accounts, a balance will be set up at the time of completion of the transaction (closing). Closing is the time when the shares are "delivered" to the buyer against the seller receiving the purchase price, i.e. performance-for-performance. In practice, this means that the purchase price at closing must be calculated on a temporary balance sheet The assets included in the calculation of net working capital are already part of the enterprise value. One must therefore not adjust for total net working capital. with a balance day a few weeks before closing, as you cannot set up a revised final balance on the same day as closing. This temporary balance, which is used to calculate the purchase price paid at closing, must therefore be updated and revised by the auditor after closing in order to be able to draw up a final revised balance sheet with a balance sheet date equal to the date of closing. This final balance forms the basis for a subsequent adjustment of the final purchase price. In practice, this means that a smaller amount of the purchase price is held in escrow, often between 1% and 3%, to ensure payment of the difference between the preliminary purchase price that is paid at closing, and the final purchase price that is calculated on the final balance set up and revised after closing.

Basically, the choice of locked box or closing accounts will determine which balance forms the basis for the calculation of the working capital, as actual working capital will be calculated on the same balance sheet date that forms the basis for the calculation of enterprise value.

It can be of great importance to the seller whether one chooses locked box or closing accounts. As an example, working capital will vary during the year if the business is exposed to seasonal variations. Another example is where the business is in a growth phase that eats away at liquidity.

3.5 Normalization – calculation of normalized working capital

When the seller agrees with the buyer about which accounting items should be included in the calculation of the working capital, the question arises as to how the normalized working capital should be calculated.

There are a number of ways to calculate what should be considered normalized working capital. This applies both to which method is to be used, as well as over what time horizon the working capital is to be assessed on the basis of. This means that discussions can arise between the seller and the buyer about which principles should be used as a basis, and there will be different considerations that must be emphasized depending on whether the business is in the start-up phase, is a growth company, operates in a sector subject to economic fluctuations, or is a stable well-run business.

To indicate the questions one faces, for a business in strong growth there will be good reasons to calculate normalized working capital using a different method than when calculating normalized working capital for a stable, well-run business.

In essence, the three most common methods for calculating normalized working capital are as follows:

3.5.1 Arithmetic average – for stable businesses

When using the arithmetic mean, normalized working capital is calculated as an average calculation of the selected period's working capital. This method is used for a business where the working capital for the business is relatively constant, which is relatively unaffected by turnover.

3.5.2 Working capital as a percentage of turnover

This method is often referred to as working capital as a percentage of the last 12 months' turnover (Last Twelve Months / LTM). Under this method, the working capital is calculated as a percentage of the business's last 12 months' turnover. This method is used where the working capital varies with the company's turnover, or operates in a sector subject to economic fluctuations.

3.5.3 Working capital as a percentage of annualized turnover

The method that calculates working capital as a percentage of annualized turnover takes as its starting point the working capital in a specific period, and grosses this up on an annual basis. If, for example, you take working capital and turnover for the last quarter, and annualize both factors, you will get a working capital that is better suited to show the working capital of a growing business. If the company's quarterly turnover is 200 and the working capital in the same period is 100, then the share will be 50% [(100x4)/(200x4)]. This is a method that is applicable where the business has growth in turnover and where the working capital increases in line with turnover.

3.5.4 Assessment

The various methods have their advantages and disadvantages, and it is always necessary to make individual adaptations depending on which business one owns and which phase it is in. An experienced M&A lawyer can therefore be an important supporter when negotiating what should be correct working capital in a specific business.

4. DEDUCTION FOR NET DEBT

Net debt is short-term and long-term interest-bearing debt (minus cash and surplus liquidity).

Basically, it is relatively easy to classify short-term and long-term interest-bearing debt, but the calculation must also include payable tax to the extent that payable tax is not part of the working capital.

In addition, one must include deferred tax / deferred tax benefits, even if this is not interest-bearing.

Surplus liquidity are assets that have not worked in the business, and which are therefore often not part of the calculated enterprise value. Surplus liquidity can, for example, be free liquidity that is temporarily placed in shares or other liquid assets. In some transactions, surplus liquidity is treated as a separate item.

In addition to the items mentioned up to now, there are a number of other items that need to be corrected, for example deferred tax, pension and transaction costs, to name a few items.

5. CASH AND CASH EQUIVALENTS

The third component to be adjusted for is cash and cash equivalents.

In practice, you often see that cash and cash equivalents are taken into account as part of net debt. But there are good reasons for treating cash and cash equivalents as a separate item. The rationale is that the seller can clear up the question of whether the cash or cash equivalents have contributed to the creation of the EBITDA, and thus enterprise value.

An example is where the business has highly liquid assets such as surplus liquidity which is temporarily placed in listed shares. Return on this type of assets is not part of the EBITDA, and thus not included as part of the enterprise value. Therefore, the seller will be able to demand extra payment for such assets when selling his business.

As we can see, cash can be placed in all three categories in the equity bridge, i.e. as part of working capital, as part of net debt, and as part of cash and cash equivalents. If the cash is part of the normalized working capital, the seller will not be paid for the cash, but if the seller manages to place the cash in net debt or in cash and cash equivalents, the seller will be paid "krone-for-krone", - literally.

6. EQUITY VALUE

By starting from enterprise value (see point 2), adjusting for the difference between actual working capital and normalized working capital (see point 3), and deducting net debt (point 4), and correcting for cash and cash equivalents (see point 5), one arrives at equity value.

The adjustments you make in enterprise value to arrive at equity value are therefore called the equity bridge.

7. ENTERPRISE VALUE – CALCULATION OF THE MULTIPLE

The starting point for the equity bridge is enterprise value, as shown in Figure 1 above.

There are many different valuation models that are used to calculate enterprise value, as mentioned under point 2.1 above. In practice, enterprise value is often calculated by taking the group's EBITDA as a starting point As we can see, cash can be placed in all three categories in the equity bridge, i.e. as part of working capital, as part of net debt, and as part of cash and cash equivalents. If the cash is part of the normalized working capital, the seller will not be paid for the cash, but if the seller manages to place the cash in net debt or in cash and cash equivalents, the seller will be paid "krone-for-krone", - literally. and multiply it by a multiple.

How to calculate the group's EBITDA, or adjusted EBITDA, is known to most people, and should therefore not be discussed in more detail here.

When it comes to calculating the multiple, it is common in practice to find comparable transactions in various databases, and calculate a weighted average where the weight of the multiple varies both in how comparable the transaction in the database is, by geography, and at what time the comparable transaction was carried out.

What is less known, however, is how to calculate this multiple mathematically, based on the individual pending transaction. This mathematical multiple can be used as an acid test or a sanity check of the multiples you retrieve from various databases. We will take a closer look at how to calculate the multiple mathematically here.

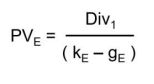

When calculating the EBITDA multiple, it is common to take Gordon's growth model as a starting point.

PVE = Present value of the shares today, Div1 = first year's dividend on the shares, kE = required return on equity (CAPM), and gE = expected growth in annual dividend on the shares (growth).

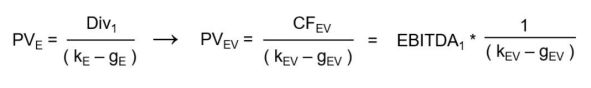

If you assume that the group's EBITDA is a good approximation of the cash flow to the total capital in the group, at the same time you have calculated the required return on the total capital, as well as calculated the expected growth in the group's EBITDA, you will be able to write about Gordon's growth formula as follows:

PVEV = Present value of enterprise value today, CFEV = first year cash flow to total capital, where one uses group EBITDA as an approximation, kEV = required return on total capital (WACC), and gEV = expected growth in cash flow to total capital, where one uses expected growth in group EBITDA as an approximation. You can then isolate the EBITDA, so that you calculate the multiple as a separate one Page 8 of 8 CONCLUSION factor.

If, as an example, you take for granted that the required return on the total capital k is 12.5% and the expected growth in the group's EBITDA g is 2.5%, you see that the denominator becomes 10%. If one subtracts the EBITDA in year 1, from the fraction, and lifts the denominator of 10% up into the numerator, the multiple becomes 10.

In this way, one sees that a modified Gordon's growth model can be used to calculate enterprise value by multiplying EBITDA by the multiple. In practice, it is therefore often heard that people talk about "10 times EBITDA", or "10 times´n".

8. CONCLUSION

The purpose of this article has been to bring out what is meant by enterprise value to equity value and bring out the various factors in the equity bridge.

Anyone who is going to sell a business may now have a better understanding of how important normalized working capital is. Thus, someone who is planning a sale of the business can adjust the working capital in the business well in advance of the sale, so that the seller can get an even higher price than the seller would otherwise have received.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.