(This article was originally published in three parts.)

Once upon a time, wealthy clients could get answers to all of their financial questions by calling their Accountant, Banker or Broker. Today it’s not so simple:

- Accountants are being crowded by "Financial Planners" and "Wealth Managers",

- Brokers have become Investment "Advisors" (but not Investment "Counselors") and

- Bankers are no longer all created equal – some are more "Private" than others.

At the top of the investment "food chain" (or the bottom, depending on your perspective) are the clients, whose needs and concerns remain largely unchanged. They still want conservative growth, capital preservation and tax effective management.

So, where do confused clients go for help in sorting out their ever-increasing options for managing the family fortune? More and more of them (like it or not) are turning to their lawyers. This is especially true for clients with first generation wealth, because building a successful business generally does not prepare them to manage the proceeds from its eventual sale. Younger generations of wealthy families, however, are also turning to their lawyers in search of clearer and more comprehensive solutions that will save time and fees in the management process and free them to spend more time building their families and careers.

The question is, however, does all of this add up to an opportunity or a liability for the lawyer in question. In most cases, it’s "all of the above." Assuming you are faced with the question, however, your choices are three. You can give good advice, bad advice or no advice at all.

As you may know, many brokers and bankers offer generous "finders fees" to professionals who refer them new business. Assuming that’s one ethical dilemma you can live without, giving NO advice is a sure way to avoid a perception of impropriety or conflict of interest on your part for recommending one broker or banker over another. Also, when markets eventually (and inevitably) turn down, you probably don’t want to be remembered for having recommended the broker who "lost" the client’s money. For these reasons, many lawyers opt out of the question altogether.

If, however, you are unwilling (or unable) to discuss the issue intelligently and suggest appropriate solutions, then you not only forfeit an opportunity to enhance client confidence, but you may even risk losing the client altogether to someone better-prepared (or less prudent) than you. At a minimum, you certainly lose the ability to "control the process" and assure the quality of the advice the client is receiving.

Your remaining option is to provide GOOD advice. Doing the necessary research at your hourly rate, however, is probably neither cost effective for your client nor beneficial to your practice. On the other hand, calling in a specialist is often an excellent alternative because it allows you to:

- Enhance client confidence,

- Escape conflicts of interest,

- Avoid blame for market losses,

- Maintain advisory "quality control", and

- Reduce overall costs to the client.

Naturally, it is important to find someone who is truly unbiased and conflict-free. This is often more difficult that it might seem, however, because commission sharing and finder’s fees are still quite common in the investment industry. If you can find such specialists, however, they can be extremely valuable resources for helping to bring a new dimension to your practice without using your own billable time.

Who are the Wealthy (& What Do They Want?)

Assuming (arbitrarily) that "wealthy" clients means those controlling at least $1 million worth of marketable securities, this includes not only individuals on their own behalf, but also private and charitable trustees, directors of various organizations and even those who are informally entrusted with looking after the financial affairs of family members or friends.

Apart from the size of their investment accounts, what do these various types of clients have in common? Not much. That’s why a thorough and unbiased "needs analysis" is essential before engaging an investment firm. This is rarely as simple as it seems, however, because most clients have acquired significant misperceptions and prejudices about the investment industry through marketing, media hype and negative prior experiences. As a result, a good deal of preliminary education is generally required to help clients understand their genuine and reasonable needs and how the various financial service providers in the marketplace might respond to them.

Investment Industry Players

Fortunately, despite their dizzying number of titles, designations and licenses, all client-service "professionals" in the investment industry can be separated into two basic categories: Managers and Advisors. At least for the purposes of this article, the clear distinction is this: Managers are licensed to solicit and accept "discretionary" mandates to trade securities on behalf of their clients (i.e. without specific permission for each transaction) and Advisors simply are not.

Managers are normally licensed as "Investment Counselors" and often limit their services to Discretionary Portfolio Management. Strictly speaking, Investment Counselors do not actually trade securities, but merely act on behalf of the client through a stockbroker, just as the client would.

Advisors, on the other hand, come in several varieties. Probably the two most common, however, are "Registered Representatives" (RR) of Securities Dealers (commonly known as Stockbrokers) and "Financial Consultants or Planners" (FC). Stockbrokers are licensed to trade stocks, bonds and mutual funds (on specific instructions from their clients), but traditionally stay away from insurance and tax planning. Financial Consultants, on the other hand, do offer general tax and retirement planning and are frequently employed or contracted as salespeople by Mutual Fund and Insurance companies.i It is worth noting, however, that an FC who is NOT employed by a brokerage firm as a licensed "stockbroker" (RR) may not recommend or even discuss individual stocks or bonds with clients. This is an important regulatory limitation that is often ignored by clients and consultants alike.

Finally, large banks often market their "wealth management" services under the euphemistic label "Private Banking." Traditionally, a Private Banker represented one of the small, privately owned European banks specializing in extremely personalized service, so the adoption of this term by large, publicly owned institutions is perhaps a little ironic. In fact, the members of the Swiss Private Bankers Association were so disturbed by the "increased and abusive use of the term ‘private banker’ by people or establishments not fulfilling the legal definition"ii that they actually trademarked the term in 1997 (at least in Switzerland).

In any case, in North America "Private Banking" has come to mean a hybridized package of brokerage, portfolio management, personal lending and perhaps limited planning services together with access to offshore subsidiaries for those who are so inclined. Although not a separate service, Private Banking is designed to be perceived differently by wealthy clients, so it may be useful to examine it separately to see if that is the case.

Client Perceptions

What do clients think of all these different players? An excellent book entitled "Cultivating the Affluent" by Russ Alan Prince and Karen Maru File explored precisely this topic by analyzing responses to an in-depth survey of almost 900 wealthy clients in the U.S.

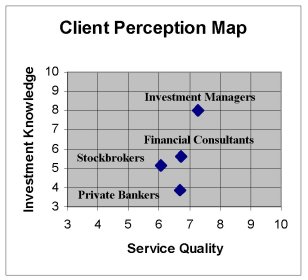

In one section of the survey, the authors asked clients to rate various types of investment service providers from 1 to 10 on both Service Quality and Investment Expertise and then plotted the results to create a kind of "Perception Map" of popular opinion.

As you might imagine, Investment Managers were given by far the highest marks for Investment Expertise. This seems logical in that they promote themselves as specialists in the area. As discretionary managers, however, they do not personalise their services in the sense that they do not seek client approval of their management strategies. Despite this "inflexibility", however, Investment Managers were also ranked highest for Service Quality, probably due to their perceived "reliability" for delivering what they promise on a timely and accurate basis.

Financial Consultants were ranked almost as highly in terms of Service Quality, but substantially lower in terms of Investment Expertise than Investment Managers. Again, this seems reasonable considering that they tend to be generalists covering a wide variety of areas apart from investing.

As you might imagine, Financial Consultants outranked Stockbrokers in terms of Service Quality, apparently due to their perceived higher degree of professional independence versus Brokers. Surprisingly, however, they also outranked Brokers on Investment Expertise, again probably due to the perception of greater independence.

Finally, Private Bankers were ranked on par with Financial Consultants in terms of Service Quality, but dismally low in terms of Investment Expertise. Both of these results are probably related to the popular perception of Private Banks as conservative, service-oriented institutions that may be out of touch with modern financial markets.

Of course, all of these are merely client perceptions and may be no more accurate than any other stereotypes. Understanding these common stereotypes, however, is an important first step in educating and counseling wealthy clients on the selection and monitoring of appropriate investment managers.

Selection Process

Prince and File’s survey results also reveal detailed information on clients’ views of the selection process. To begin with, 80% of respondents felt that investing, like law or medicine, is best left to trained professionals. In fact, over 90% agreed that individual investors each have unique needs and that selecting a good investment manager is more important than selecting individual investment products.

So, what do wealthy clients typically look for when selecting an investment manager or advisor? More than 75% of the respondents said they looked for the following:

- Overall expertise (91%),

- Careful needs analysis (89%),

- Appropriate investment style (84%),

- Trustworthiness & Discretion (82%),

- Attentiveness to client concerns (80%), and

- Desire to have a long-term relationship (75%).

Certainly, these are all important qualities for an investment manager. The problem is they are also practically impossible to measure – certainly before engaging the firm. On the other hand, less than 15% of clients surveyed felt that the following criteria were important:

- Assets under management (13%),

- Manager’s personal investment (10%),

- Management Costs & Fees (9%),

- Manager Innovation (6%),

- Detailed reporting (5%), and

- Relative risk of investments (2%).

In contrast to the factors in the first group, these are both measurable and useful in assessing important aspects of a manager’s resources and capabilities.

So if the criteria in the first group are too vague and those in the second more or less ignored, then what are clients really looking at? Too often it boils down to perhaps the two least "scientific" factors: personal references and past performance data.

References from a friend or professional advisor (lawyer, accountant, etc.) seem to take the place of all of those important but immeasurable factors such as "expertise" and "trustworthiness." While this may seem reasonable, research shows that clients are most likely to give referrals during the first few months after selecting a new manager possibly due to hopeful enthusiasm for the new relationship, anxiety over the recent change or both. Whatever the reason, these clients usually do not have enough experience with their managers to do more than repeat the promotional information they so recently heard themselves.

Past performance data is perhaps the most misunderstood and potentially dangerous of all the elements considered by clients in search of a new manager. Suffice it to say that without proper and unbiased interpretation, they are worse than meaningless because of their potential to seriously mislead potential clients. Look for more on this below.

Erik Yeargan is a licensed attorney and an experienced Swiss Private Banker who works with Montreal lawyers and accountants to help their clients select and monitor their Canadian and International wealth managers in order to obtain appropriate and accurate services while avoiding unnecessary risks and fees.

Managing the Managers

Having examined some of the reasons why wealthy clients often seek their lawyers’ advice on money matters and some of the issues and opportunities this can raise for lawyers, it might be useful to look briefly at one example of a sound process for selecting an Investment Advisor or Manager. Naturally, this process is circular in that it is repeated at the end of each cycle to ensure that the investment services continue to meet the needs of the client. This process can conveniently be broken into five stages:

- Policy,

- Profile,

- Philosophy,

- Process, and

- Performance.

Policy: Establishing Client Needs

As noted earlier, 90% of the wealthy clients surveyed by Prince and File felt they had unique needs and that it was extremely important for prospective investment managers to conduct a careful needs analysis.

This is certainly true because every client does have uniquely complicated needs and tolerances regarding a wide variety of basic investment issues such as time horizon, volatility, liquidity, capital preservation, returns, financing, accessibility, transparency, taxability, etc. In addition, some "clients" are actually groups of stakeholders (spouses, co-trustees, co-beneficiaries, board members, etc.), each with his or her own perspective on these issues. The ultimate purpose of this process is to answer one essential question: "What is this money for." Once that question has been answered, however, a new one arises: "Who will be responsible for the day-to-day management?"

For a wide variety of reasons, clients often decide that they need more than an "advisory" relationship with a stockbroker to accomplish their financial goals. For example, the account may have grown too large (or too small) since it was opened with a broker, the client may lack time, training or interest in managing the money, there may be a conflict of interest in the case of a fiduciary or trustee, there may be a potential dispute among beneficiaries or inheritors, or the client may simply be seeking more personalized attention and greater expertise.

Whatever the case, if discretionary management is called for, then all of the client’s needs and tolerances should be carefully organized in a written Investment Policy Statement. This document provides the "rules of the road" for the investment manager who will take over day-to-day management of the account. In addition to background on the funds and the client (e.g. investment experience, source of funds, other interested parties, etc.), this document should cover certain basic issues like:

- Volatility and capital preservation sensitivity,

- Relative vs. absolute return preferences,

- Liquidity and accessibility concerns,

- Time horizon(s) for invested funds,

- Growth and income requirements,

- Asset allocation parameters

- Estate planning strategies,

- Regulatory constraints,

- Tax status of accounts,

- Benchmark selection, etc.

Profile: Structure of the Firm

To begin with, management firms come in all sizes and each has its own strengths and weaknesses. Size wise, large banks may offer more international services than independents, but far less objectivity and personalization. Even independent firms range widely in size, however, so there is considerable choice on that basis alone.

Other important factors include firm ownership structure and sources of revenue, composition and remuneration of the management team, core and related services, strategic alliances, profiles of the current client base and even quality of the work environment in the offices (happy employees do better work). Also, for independent firms, succession planning is an important issue because clients who select such firms are rarely pleased when a larger institution acquires them.

Philosophy: Principles and Strategies

Even within specific segments of the market, different managers often have very different styles and philosophies of investing. For clients, the important thing is to find managers who can articulate the principles of their philosophy and demonstrate their ability to implement those principles. Of course, the manager’s style must be both clearly understood by clients and suitable to their needs and tolerances if there is any hope for a successful long-term relationship. Here is a short sample of some equity "style" points that might be presented in an investment philosophy discussion:

- Value vs. Growth

- Passive vs. Active

- Foreign vs. Domestic

- Hedged vs. Unhedged

- Large Cap vs. Small Cap

- Top Down vs. Bottom Up

- Fundamental vs. Technical

Process: Implementation Methods

The Investment Process is the manner in which the firm implements the principles of its Investment Philosophy. This process must encompass activities at both the firm and individual manager levels because it does no good to have a firm-wide policy that is not respected by the individual managers. Of course, the key issue is consistency. Clients need to be assured that their assets will be managed according to the firm’s stated philosophy as well as the agreed upon Investment Policy regardless of which manager is currently responsible for the account. Some of the issues to consider are:

- Account manager (qualifications, experience, client load, firm ownership, etc.),

- Portfolio construction (number of holdings, consistency w/model, etc.),

- Technology & tools (security screens, portfolio tracking, etc.),

- Dispersion of returns (across asset types and client accounts),

- Compliance procedures (regulatory, investment policy, etc.),

- Research sources (brokerage-related vs. independent, etc.).

Performance: Past, Present & Future

Performance seems to be the most misunderstood and abused part of the whole manager search process.

By now, many clients can recite the infamous mantra of the investment industry, "past performance is no indication of future returns," right along with the managers as they present their performance data. Based on Prince and File’s survey, it would even seem that clients have begun to believe it, because only 25% named performance as a top criteria for manager selection. Why then, do so many clients seem to focus on this factor so exclusively during the search process?

Frustration is probably the main reason. After all, even though 75% of surveyed clients agreed that expertise, management style, needs analysis, etc. are more important than raw performance, those are arguably impossible to measure with any kind of accuracy whereas annual returns are simple to quantify and seemingly simple to understand. Add to this the long list of books, articles and web sites that rate thousands of mutual funds almost solely on past performance and busy clients can hardly be blamed for yielding to the temptation of relying on such a seemingly simple and pertinent indicator of manager ability.

So, if it’s true that "past performance is no indication of future returns," then what is it good for? The answer is, "absolutely nothing" without standardization and interpretation.

Interpretation includes, among other things, adding context and relevant benchmarks to performance data. After all, performance is not good or bad in the absolute, but only relative to pre-determined benchmarks, e.g. another manager, an index, or simply a fixed target. Interpretation also means, however, presenting other aspects of performance beyond simple returns, including relative volatility, manager drift, market timing effects, etc.

Because interpretation often involves comparisons, standardization of performance data is extremely important. Adjusting for various factors such as time frame, management fees, account composition, style definition, mandate qualification, etc. is what allows these comparisons to be made on an "apples to apples" basis.

Conclusion

For a variety of reasons, it seems that more and more clients are searching for discretionary investment management relationships. Because of the complexity of this task, however, it is not surprising that many of them end up relying on the advice of lawyers and accountants to guide them. While this may be a good opportunity to enhance client confidence and expand your role as a key advisor, it is also probably outside of your core practice. By bringing in a specialist, you can effectively respond to your clients’ needs while also avoiding conflicts of interest and loss of billable time, which could be more effectively spent working on other matters.

Footnotes

i A few Financial Consultants/Planners are “fee-based,” meaning they charge their clients directly rather than accepting trailer fees and commissions from the sales of Mutual Fund and Insurance products. They are definitely the exception, however, and often could more appropriately be categorized simply as accountants specializing in tax, retirement and estate planning.

ii http://www.swissprivatebankers.ch/index.cfm?page=/abps/members&language=EN?word=trademark

Erik Yeargan is a licensed attorney and an experienced Swiss Private Banker who works with Montreal lawyers and accountants to help their clients select and monitor their Canadian and International wealth managers in order to obtain appropriate and accurate services while avoiding unnecessary risks and fees.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.